2024 Online Fiction Contest Winner: Circulation Line

By Jisoo Hope Yoon

In the dark I dream only of bottomless mimosas. When I wake my neck is stiff, a sharp sideways pain like the grind of a screw rusted orange. I right my head and immediately lock eyes with a middle-aged man sitting across from me, too-tight-suit revealing the contour of a soju belly from nights downing pork grease and alcohol to satisfy his boss’s whims. He will do for today: my morning fixation. I make silent guesses at his salary, approximating his position on the corporate ladder, noting the price of his watch. My calculation is cut short when he notices my stare, breathes a curse through the corner of his mouth. I’m okay with this. That’s the way things are here, I’ve been told. They will always stare at foreigners, but that does not give you license to stare back.

The train rattles to a stop and the man gets up, sways a little too close to me before getting off, mutters something I can’t quite make out. If you were here I would simply tilt my ear towards your lips and you would translate for me. That pause as you choose your words, how I’d savor it. How I miss it now, so far from you, and so directional. I was never meant to travel alone. You could blunt any violence, love; I would rather be at your mercy than anyone else’s. It is my three hundredth day on Line 2 and my Korean has not improved. If I ever get off, I swear to myself, I’ll go get some fucking lessons.

∞

Fucking lessons, you joked when you first came over to my place. Lessons of fucking, about fucking, disguised as anything other than fucking. We were matched as language exchange partners at the library I worked at in Philly, and in place of pronouns, I offered my tongue. I would have given you my English directly if I could, if only, if only the wetness could coalesce into language in your mouth. I never cared for it anyway. My English, I mean. Language I do care about, and wetness. I never told you this, but I had no interest in learning Korean before finding your name on the bulletin board. I just thought you were handsome. I’m no freak, and you made sure of this when we first talked. Are you one of those K-pop fans, you asked, and I was like no but what’s wrong with that, and you thought for a very long time because the expression was eluding you and because you never settled for Plan B, and finally you grasped it and said: because that is cringe.

I am reminded of this, the incongruity between that word and your serious face, as the train thunders through the dark Seoul underground, lethal and electric. My gaze snags on a girl, thick bangs, low ponytail, that puffy black jacket everyone wears. Student, I think, but then the cigarette in her hand. She’s twiddling it like a pen, and I understand then that she can’t wait another second to sprint aboveground and light it. I know a thing or two about addicts. I eye her with a soft smile until the train squeaks to a stop, wishing her a hellish, perfect drag in the outside world I no longer have access to. The doors open. But wait. She stands rooted in her spot, like she’s bound by something invisible, like the doors may have well been closed, but only for her. People squeeze past her and through the doors, shooting annoyed glances. I spring to my feet in a moment of uncanny recognition: three hundred days and maybe my first companion, someone to share this purgatory with. She whips around. She says: 그쪽도 나랑 같죠?

∞

Joanna, I tell her when she asks for my name. I catch her in her third escape attempt: she drifts into my train car after missing her stop and the one after that. She sinks into the seat next to mine as I help her process her new predicament, acting like some sort of prison elder. I tell her not to bother looking for other exits, that I’ve tried everything already and she ought to preserve her energy. Walk all the way to the front, and the conductor will ignore you. Walk all the way to the back, and you will find no door. Try to grab one of those ‘in case of emergency’ hammers off the window and it will vanish in your hand, not to mention everyone will look at you weird, like you might be some deranged political protester about to delay their morning commute. The girl has a much harder time accepting her reality than I did when I first got stuck, and I wonder why. She doesn’t have the look of an optimist; lacks those characteristic eyes which somehow reflect back something more than the light that entered them. No, I can see why she is here with me. Poor girl, she might never get another hit of nicotine for the rest of time.

I ask her for her name in English because I can already tell her English is better than my Korean.

“진,” she tells me, “이진.”

“Like gin, the liquor.”

“No. 진.”

“Like chin,” I say, pointing to mine.

“It’s 진. J-i-n.”

“Oh,” I nod, pretending to understand, though gin and Jin sound exactly the same. She reminds me of you, though her English is more textbook, yours more greased-up with that study-abroad money. No, it’s the methodical tenacity, the near-zero margin of error, like the time you took me out to a family restaurant for our second date and you googled the nutritional information of every ingredient listed under every dish before making your choice. I looked up to the way you engineered your days. I thought that was what I had been missing my entire life: the ability to plan in advance. And I your perfect American girl, my spontaneity blue, sexual history blond. No matter how often you insisted otherwise, I know this to be true: you chose me, not the other way around.

∞

Around Dangsan, the stop where Jin was supposed to get off to transfer to Line 9, she always gets a little restless, leaving our conversation midway to pace or attempt another exit. This persists for weeks and I ask her about it when it gets annoying. Her final destination is Noryangjin, which I know holds the nation’s largest seafood market. What I didn’t know is that it is also home to thousands of young Koreans preparing for public service examinations, studying all year long to beat impossible odds and snag a coveted government job. The work is tedious and the pay low, but passing the exam means you’d never work past 6pm or get fired in your lifetime. Which apparently is enough to attract hordes of twenty-somethings into cramped dormitory housing where they eat instant noodles twice a day and spend the rest of their waking hours swallowing information.

Jin tells me she has failed this exam six years in a row, her practiced monotone betraying no bitterness as she makes this confession. She has run her parents’ meager savings into the ground. They paid for a decent dormitory at first, free kimchi and free of roaches, but she moved somewhere higher up the Goshichon hill after twice not making the cut, and last year, she settled for a semi-basement room. I give her a sympathetic look and she defensively tells me how competitive the exams are. “Like a needle hole,” she describes the odds, “like a hole in a needle which you use for sew. One person pass, nineteen fail.” The English portion of the exam is what held Jin back every time. It consists of grammar, vocabulary, reading, and “life English,” and is altogether considered the most difficult section. It is everyone’s primary enemy, statistically the biggest reason why some enroll over and over again.

∞

Again, Jin asks me when I finish telling her the story of my final destination. I pause to consider. It’s not the contents of my story that are slippery but the order in which they must be told, the trembling finger which must eventually fall on a point of beginning, the pulse, the moment from which history propagates. So I oblige, tell Jin all about you and me, except I begin this iteration in our own half-basement in Sillim, where we drowned in takeaway containers and rotting meat, the trash climbing over and eventually into your Gibson electric guitar, your last prized possession, something you believed in even as you lost faith in me. Is this what I moved here to do, I yelled at you. Lock myself in this tiny ass apartment getting fat with you. You yelled back that I was the one who had bought the ticket to Korea, that I chose to follow you here, that you were ready to leave everything American behind. Why didn’t I just let you go back? You screamed into my ear until I wasn’t sure which of us had originated the question. And like every other day, once we had torn our vocal cords raw, we ordered Chinese food and fucked as the motorcycle icon on your delivery app inched closer to our address, the only address, our beloved black hole of wicked rapture.

And that’s why I was going to get off at Hongdae, I tell Jin, who is staring at me wide-eyed. I’m not sure whether her hyper-focus comes from needing to work twice as hard to parse the narrative from my English, or from sincere shock at the ugliness of my life. She asks why I wanted to get off at Hongdae when Sillim is halfway across town. I tell her my boyfriend had his first gig in two years at one of those indie clubs. I was on my way there. Until I got stuck here. I can sense she feels bad that I missed such a momentous occasion, and I’m quick to tell her it’s okay, he wasn’t going to show up anyway. I’m right, aren’t I? You were too far gone. A dream, like a second language, evaporating with such callous ease. I watched you let it go. (It could be said, of course, that I was eager to do this watching, that I had forsaken my own dreams the minute I boarded that flight.) Jin looks at me all confused, says I could easily find another boyfriend or a job here, being American. Oh my, she knows nothing. Says she really hopes I’ll get out of the train soon and find my way, that it must be within reach; she’s sure we’ve been given this time on the train for a reason. Oh my. What a nice girl.

∞

Nice girls don’t sit like that, a mother chides her daughter, who looks eight at most; those jelly sandals. Binaries are easiest on the foreigner's ear: nice and bad, girl and boy, do and don’t. I prickle with the modest thrill of comprehension as the girl pulls in her knees from the manspread they were in. I wonder where they’re coming from. I’ve never seen a kid here so late at night, the train making its final counter-clockwise loop, which I can always identify for the number of inebriated college kids who stumble in out of breath, cheering when they make it on before the doors close. Those are the tame ones. The vicious drunks get on the first train of the day, their nasty, unhinged breaths waking us without fail around 5 in the morning.

Jin and I played a game today. We sat side-by-side in the corner so we’d have a full view of the car, making bets on which passengers would give up their seats when someone more visibly deserving of those seats got on. Pink shirt, I’d say, and Jin would parry, no, glasses. This is a world populated by clothing and not the people they contain. The little girl is jelly sandals, the mother counterfeit handbag. I am layers upon layers. Jin is all black, but now she shakes off her jacket to cushion her seat with it, preparing for sleep. She says, I am now here almost two months, so it is April outside maybe. It is April here, she corrects herself, and I admire that: her grip on the above-ground, the larger motions of its calendar. I count my exile day by identical day and never lose the number, repeating it to myself every night when I feel the first tide of sleep wash over my face. So close now to three hundred and sixty-five. So close and yet what would it change. The train rattles on, and when my eyelids drop their weights like clockwork, the last thing I see through my half-shuttered view is Jin sitting across from me, her and that row of seats tilting and tilting until I am returned to dark, that resting place where categories go to die.

∞

To die without a name must be a luxury. Sometimes I take the pink seat on purpose, even when the car isn’t full, and feel my body mold itself to the name Imsanbu, Pregnant Woman. And I mean crayon pink. Ugly, that garish shade, and at least one per row: seats painted for women, potentially bearing life, potentially in need of exceptional protection. And me, in this place. I am exceptionally pale. Long-limbed too and fragile. Back home I was gangly, here I’m just slim; back home I was sickly, here my skin’s milk. There are places where pallor can be wielded like a power, and I may lack the violence to swing it around, but who could blame me if I held it, simply held it, like a shield.

Would you believe me if I told you I knew this would happen? I knew the moment you asked me to choose an English name for you, back in that library where I caught you studying English in the most dogged, witless way possible: two dictionaries side-by-side on your desk. Your real name was difficult to pronounce for your craft-beer-drinking peers in that master’s program, too many vowel combinations for their music theory brains. You wanted a name, like a nutritional label, a diagnosis. It was too much power for you to give away so readily. I took it like a bet. Began my silent catalog, things I could hold over you down the line if I wanted. I took you like a bet and I suppose I have wagered my life. I gave you a name I could eat.

∞

I could eat an entire fried chicken, I tell Jin. The foods are conjured up with ease: being inexplicably shut in a train for the foreseeable future will do that to you. Topping Jin’s list is kimchi fried rice in a shallow pool of melted mozzarella. Topping mine is deep dish pizza, followed by butter chicken with garlic naan. Followed by Korean fried chicken, the sticky kind, which tops Popeyes, which is a lot. Or spicy tuna on crispy rice. Tamales with sour cream. Tiramisu. I’d even settle for dino nuggets. All these things you could probably find on the Cheesecake Factory menu.

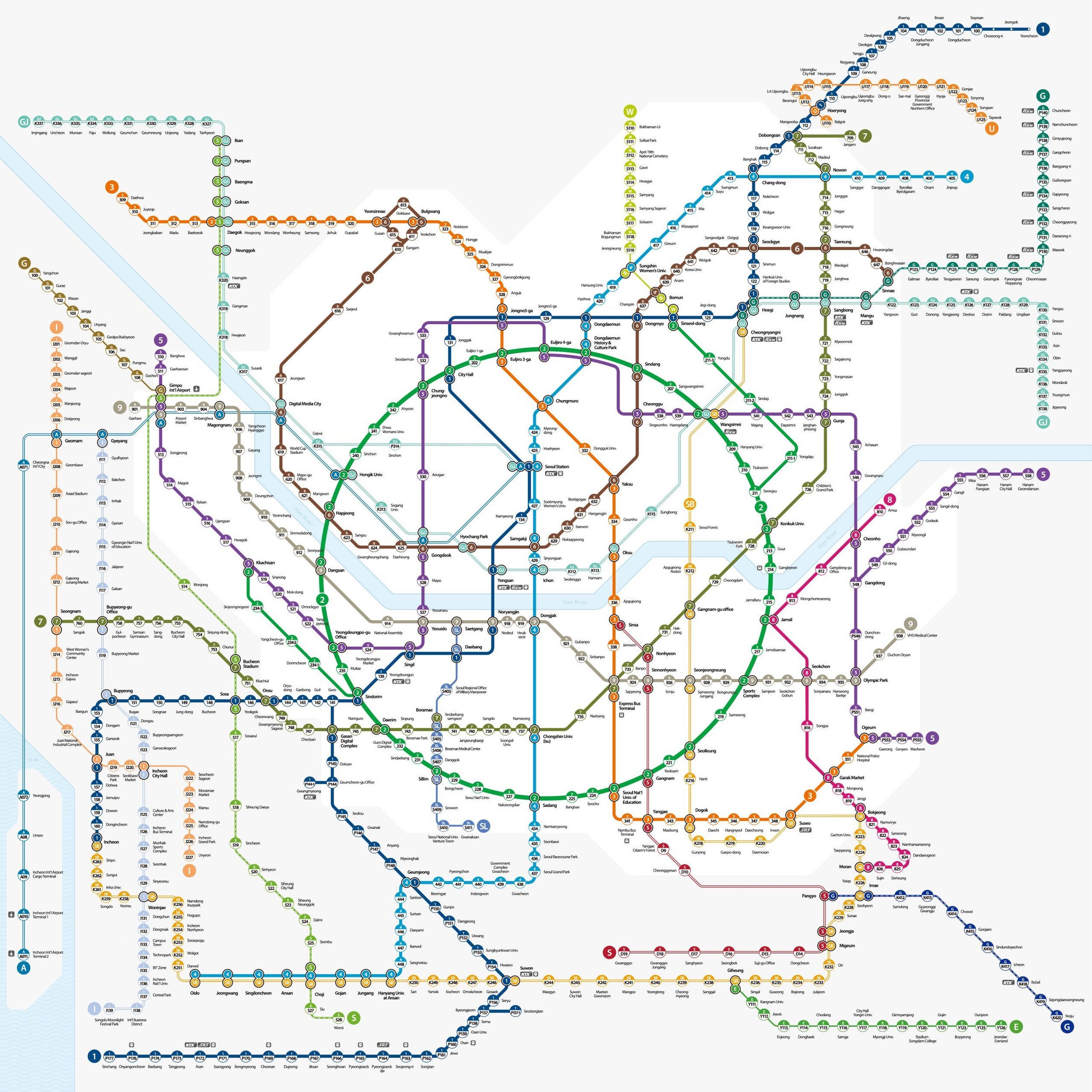

In my next life I’ll worship an air fryer. That is, if this train will let us die, since it clearly won’t let us live. I must be going at least a little crazy because I don’t realize I said that out loud until Jin responds, yeah, or we will forever just… She trails off and draws circles in the air with her index finger. What does that mean? She explains we’re on the 순환선, the 순환 line. I ask again and she struggles to explain 순환, she says like blood, like how blood goes around your body? Circulation, I offer, and she takes it. Line 2, the only circulation line of Seoul, the only one you could theoretically ride forever, from Hongdae to Dangsan to Sillim only to find yourself right back at Hongdae.

∞

Hongdae is for young blood, you said when you first took me there. We had just arrived in Seoul, moist-skinned and bearing possibilities. I could have gotten a job teaching English to kindergarteners. You know I hate children but I would have done it; I would have done a lot for you then. It was you who said no. You were gonna make it big. You didn’t study in America for nothing. Street musicians boasted high notes and I folded my body into your arm as we wove through the crowd; I knew you liked that. You said this was where you and all your artist buddies lived in your 20’s, shared two packs of ramen between five. What about your family, I asked, didn’t you ever eat with them? I heard Korea has a collectivist culture. You smirked and said didn’t you hear the news, we’re trying to be more like America.

Everything that makes this country run lives below ground. Even I know this much. I love the way you say my name. Jo-ah-na, sometimes Jo Anna, like it was always a Korean name, like I could always be a different person, requiring only the slightest re-orientation. We, too, could be different. I readily served as your conduit to the American experience and I believe there is a world where you would do the perfect reverse for me here, if only I had depended on you a little less, if only you hadn’t gotten me to start drinking with you, if only I hadn’t lied about liking your music, if only I hadn’t encouraged you to ignore your family’s calls, if only you hadn’t shoved that pizza box across the table and then said in disgust, why are you looking at me like I hit you or something. I cried until you felt bad and apologized, but of course I knew I could win every argument if I wanted to. Of course; we only fought in English. But if only we came from the same place to begin with. If only we were still in our twenties. Then maybe we would have lived the story we should have.

∞

We should have worked harder, Jin says, and I’m not sure what she means. She’s got her hair scrunched higher than usual, this intense, disembodied stare scaring off whoever meets her eyes. She says she’s ashamed she’s been riding this train for so long without attempting more ways to get out, and my first instinct is to say then what does that make me, but instead I just give her the same bored lecture about how I’ve tried everything already. She nods in sincere agreement but goes off to walk around the train anyway. When she returns, I spare her the embarrassment of having to recount her failure. I don’t say anything at all. She proposes we pass our time teaching each other our languages. It would help with her exam, and maybe it would help me adjust to this place without my boyfriend. I’m a little surprised Jin wants to give the exam another shot. She gets all quiet before telling me she was on her way back to Noryangjin to decide whether she would enroll for the seventh time, or, or, something else. Give up? I offer, and she says, something like that. (She must have learned that expression from “life English.”) So why keep studying for an exam you might not take? She thinks for a minute before saying, I can keep working on something, even if it will never happen. It is more about what I do now.

I could never understand Jin: I was personally never so stupid, not even at twenty-seven. But she talks to me the whole day about growing up here, like I am a regular tourist who dropped her bags here yesterday, and this simple distance comforts me more than anything. This is the land of six-year-old premeds. Where one in twenty live in complete isolation, never seeing daylight or talking to anyone all year. Where the sun shines brighter each passing decade and leaves more insidious shadows. I learn about Jin’s childhood friend with a luxury brand obsession which is running her into debt, I learn about Jin’s mother and how she fell for an insurance scam at forty-five, I learn that Jin would frequently spend her budget on cigarettes over meals, and who am I to judge? No one, I am no one.

∞

No one belongs in transit, and certainly no one deserves to be here forever. But you could always be here if you wanted, like the hunchbacked retirees who do nothing all day but freeload. On Jin’s eightieth morning, I know upon waking up that she is about to leave. When she stands up and announces she is ready to go, we are approaching Euljiro 3-ga. She decides to get off instead of waiting for Dangsan. A drawn-out farewell is bound to be awkward, so instead she tells me Euljiro is the old part of town, and that she hasn’t been there in six years. As if this should console me. She hasn’t been anywhere other than Noryangjin and her parents’ home for six whole years. Joanna, she says, do you think time has passed out there, because if so I may have missed the enrollment deadline for this year. Obviously I don’t know the answer.

The last thing I ask before Jin leaves is what she said when she first saw me. She said something in Korean and I couldn’t make it out. Jin tilts her head, thinking, but the train brakes and screeches, and she doesn’t remember, and the doors are open, and the people, and the exit, right there. Goodbye, Joanna. I wish I could take your place here sometimes so you could see the sun.

∞

The sunlight must come in, you insisted when we were looking for flats. I said it didn’t matter, I cared more about space and maybe a big closet we could convert into a recording booth for you. You dismissed my concerns with a wave. People here avoid light their whole lives because they don’t want to tan, you said. But it’s the most important thing for a house. I said we don’t call these houses, they’re studio apartments, and you went on talking about how a house with lots of sun, it’s a sky-and-ground difference. You mean the difference is night and day, I offered, and you just laughed and said yes, the sun makes the difference between night and day. That time I chose not to clarify what I meant; thought that understanding was better left beneath the surface. You held my face still laughing and said Joanna, Joanna, I can see you better in the sun.

My dear, to this day I wonder why it was I who got stuck and not you, here, a trail of light threading through a loop, this crochet project from hell. Are you still in our semi-basement ordering junk to your doorstep? Are you fucking some other girl, better yet another foreigner? Given the chance, I would not hesitate to take your place. I would trade tongues and trains with you, leave you here on Line 2; you can take my pink seat. I never aim to kill, but don’t you think it’s your turn to live in the dark.

About the Author:

Jisoo Hope Yoon is a writer, translator, and theater-maker from Seoul, South Korea. She is excited about language, lay conversations about physics, and stories of women making their lives their own. Her first novel is in development with support from Stanford University.