Review: The Malevolent Volume by Justin Phillip Reed

By Kai Karpman

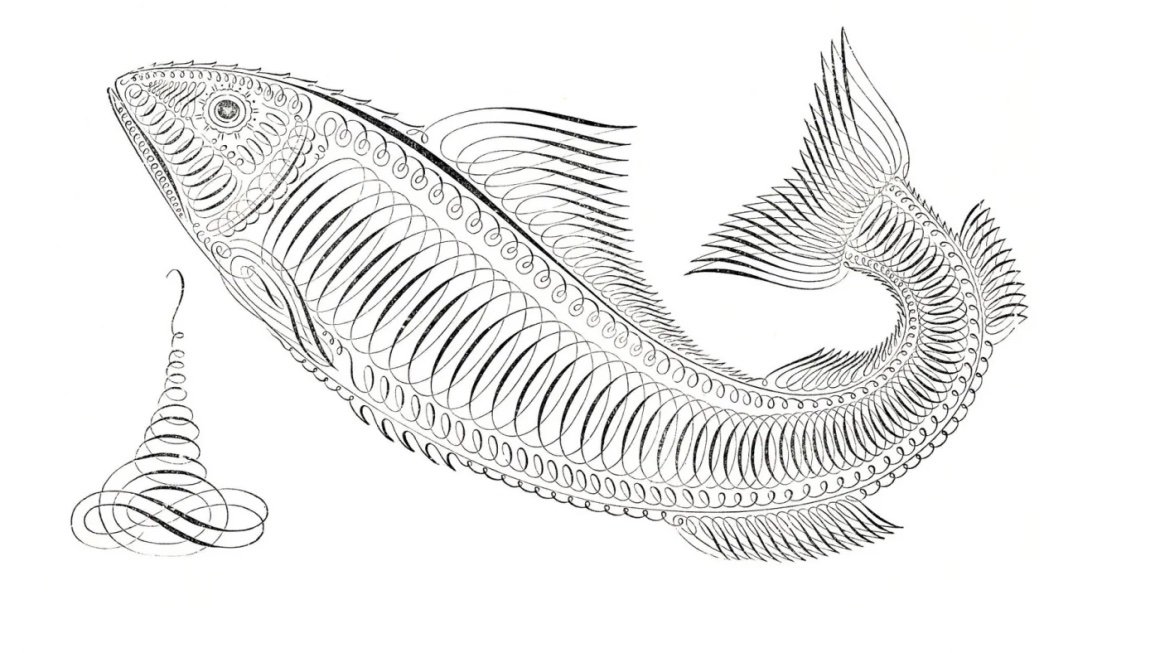

In his new collection, The Malevolent Volume, 2018 National Book Award, and Lamba Literary Award Winner, Justin Phillip Reed, delves into the underbelly of identity, poetry, religion, myths through the lens of a queer, Black American. A constant theme of The Malevolent Volume is man transforming into a monster, either classically mythic like a Gorgon, or a newly invented creature. In this collection, Reed accepts and moves deftly through anger, cultural truths, contemporary references, and never turns away.

The poet shows an acute awareness of the poets who came before him and the violence that has saturated the literary canon. In response to Sylvia Plath’s “The Jailer,” Reed writes in “Man in Black” that “ I am made, in this skin, of less water/ than is mass of dark matter in all of space. Men/ in black occur, poet” (57). Here, I argue that he responds, in part, to Plath’s racism when she writes “Pretending I am a n*gress with pink paws,” but also to her question “ What would the dark/ Do without fevers to eat?” In response, Reed suggests that the “darkness,” being anger and pain, can exist as largely as all of the universe can, untamed and unending, as it can within the poem’s speaker.

However, Reed is also a writer who recognizes and employs other poets with immense respect. In “Head of the Gorgon”, the poet pays homage to Audrey Lorde’s “Coal,” writing, “the iris’s loose grip on my face on the pit that held that my face, which was/ stunning coal-hard in all that it had borne, a monstrous feat” (44). Though the speaker claims that becoming “coal-hard” is something monstrous, I argue that we are meant to understand the strength and stunning power that it takes for a man to become coal.

Furthermore, Reed reflects upon the cannon that comes before him by inventing a new form of writing for this book which he calls “consonantal anagrammatic slant homeoteleuton,” or rather, “Cash.” He explains that “Cash” “ends (a line) in a word or phrase composed of the same set of recycled consonant sounds” (89) like he does in the poem “What they Called us was our Name.” In this way, Reed remains conscious of form and literary history while never kneeling to it, rather, he reimagines and challenges forms that came before him.

The poet paints an image of the speaker as a violent monster in parts of this book. In “I Must Be Some Kind of Impossible”, he writes “Deny I’ve ever/ been other than wraith or rare/ talent of meat” (14). In lines like these, Reed takes on a monstrous persona in order to explore monstrous topics, like gun violence, climate change, and racism. Expanding on the creation of his “monster” in “The Personal Animal” he writes “My monster had no first breath/ and none after” (53).

In other poems, like “What’s Left Behind After a Hawk Has Seized a Smaller Bird Midair,” we are allowed a brief glance into the romantic life of the speaker who notes, simply, “I like men who are cruel to me; men who know how I will end” (23). Simply put, not even love escapes the violence inside and out of the speaker.

The theme of darkness recurs throughout the book. In “When I Was a Poet,” the speaker claims “In darkness, mine was not a linear condition./ Mine was the express mission of uncountable spirits” (72). Appropriately, this poem occurs in a section of the book printed on black paper with white words. Elaborating on the theme of darkness, in “Man in Black”, Reed suggests that “Black is the nature of space” (56). In these lines, the poet complicates our notions of darkness as bad, light as good, and maintains a fascinating nuance throughout the book.

Ultimately, I see The Malevolent Volume as a necessary book for our moment. It conjures anger, strength, revolution, identity, and love, and speaks to all of these themes with a confident knowledge of their history, present, and literary significance. Reed succeeds triumphantly in this difficult navigation.