God’s Touch in Nicolette Polek’s Bitter Water Opera

By Ali Banach

The work’s size, its breathless metaphors, and its coquette-ish design all point toward contemporary trends that have spawned due to digitally-minded, attention-deficit reading lives. However, as a departure from other contemporary fragmentation, the book’s preoccupation with mysticism creates an internal justification for such formal choices.

To The Stars & Other Stories

As one of the early Russian Symbolists of the late nineteenth century Sologub—like his artist in “The Lady in Shackles,” another story in the collection—is of paltry fame but important talent. Better known for his poetry and novels, he’s credited for bringing the cynical and macabre motifs of Western Europe’s fin de siècle to Russian literature.

“True Life” in the Country of the Imagination

Poetry and terror are so interwoven, it is impossible to extricate one without disturbing the other. They run into each other, borderless and pervasive, like music, or scent.

The Poetic Science-Nonfiction of Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Undrowned

Alexis Pauline Gumbs actualizes how marine mammals survive and how they die in a capitalistic society as one in the same with Black survival and death. This might sound conspiratorial—because it is. Yet this book truly is a scientific guide on marine mammals.

Through the Eyes of Winged Things: The Birds and Ghosts of Jess Richards

Jess Richards’ memoir Birds and Ghosts is peppered with pencil sketches of birds—peppered because the specks of bird appear like grains of pepper, coalescing into network structures. Poetry, lyric essay, memoir, prose poetry, occult reflections, and sketches join to form a map, a network, shaped like a brain by connections and synaptic firings.

The Horror of the Ordinary in Emma Cline’s The Guest

The Guest is all about nonattachment. It follows a twenty-two-year-old woman named Alex as she is expunged from the home of Simon, the wealthy older man she has been staying with for the summer. The narrative action clings, as though in real time, to the five days she is left to wander the “wilderness” of Long Island’s East End, until a party on Labour Day, when Alex hopes to re-attach herself to Simon, and the trappings of his rarefied life.

History and Homeland in Monika Helfer’s Last House Before the Mountain

Austrian writer Monika Helfer’s 2020 novel Die Bagage—recently released in English under the title of Last House Before the Mountain (Bloomsbury, April 2023), and translated by Gillian Davidson—is a story of home and homeland, of belonging and alienation, of secrets that span generations.

Review: Yesterday by Juan Emar, Translated by Megan McDowell

It’s an exciting literary event when a translator resurrects a writer from the obscurity of the past. To our benefit, this is exactly what Megan McDowell does with her new translation of Juan Emar’s Yesterday (New Directions, April 2022), a novel whose wonderfully frustrating exploration of the difficulties of communication comes at a time when we are reconceiving our social relationships in a post-pandemic world. As Emar’s first substantial introduction to the American reading public—fifty-eight years after his death—Megan McDowell’s translation pays deft tribute to the levity, complexity, and despair of Emar’s prose, while maintaining the intellectual fortitude of a text that asks us to reconsider fundamental conceptions of identity that undergird both the popular novel and, by extension, our understanding of ourselves.

Fire Season: Selected Essays 1984-2021, by Gary Indiana

In Gary Indiana’s 1989 novel Horse Crazy, the narrator’s sociopathic crush finally shows him his first large-scale artwork: “an arrangement of six different male types: college preppie, Kennedy-type young lawyer, bohemian, blue-collar worker, and so forth.” The narrator soon realizes all six faces belong to Ted Bundy. “Such is the ambition of American society, that a person who runs out of control in this manner can effortlessly impress those he meets as a paragon of desirable national qualities.” Indiana is forever associated with his 1985-1988 run as art critic for the Village Voice, but he is primarily an artist, and the long bibliography of plays, films, visual art, and fiction he has produced since often focuses on people “out of control.” His best-known work is a trilogy of “deflationary realist” true-crime novels. Yet there is a difference between those who commit crimes of desperation, and those who act in the relentless pursuit of power and wealth, or, like Bundy, for no reason at all. In Fire Season, a voracious, scathing collection of Indiana’s reviews and essays, Indiana has dueling subjects: the cartoon villains of the neoliberal order, and the artists making serious work in spite of it.

In Ocean Vuong’s Poetry, an Ocean of Moving Elegiac Paradoxes

Undisputedly, the years have been at once kind and brutal to Ocean Vuong. I say kind in the sense that, from a career perspective, Vuong has ascended to the peak of literary prominence at a pace and to heights few contemporary poets can match. Along the way up, he’s accrued a faithful audience, struck late-night talk-show stardom, and garnered prestigious awards, a T.S. Eliot Prize and a MacArthur Fellowship, among countless others. But I also say brutal, in that violence and loss continue to plague Vuong’s life: he’s had to contend with the harsh realities of growing up in poverty, as an immigrant and former refugee from Vietnam, and as a bookish queer boy navigating through a largely unsympathetic society.

Hanya Yanagihara’s To Paradise: An Epic Novel For All Queer Times

In his 2015 review published in The Atlantic, Garth Greenwell heralded Hanya Yanagihara’s previous novel, A Little Life, as potentially “the great gay novel,” praising its perceptiveness in depicting the gay male experience in America and positing that the book was “the most ambitious chronicle of the social and emotional lives of gay men to have emerged for many years.” To some extent, Yanagihara’s latest novel, To Paradise, might be considered an even greater gay novel. Not only is it queer in its foregrounding of gay protagonists and socio-political themes of discrimination, non-traditional relationships, the AIDS epidemic, and racial and class-conscious intersectionality, but also in its upending of literary forms and transgressive world-building. Yanagihara excels at blending the recognizable with the inventive and also at times the absurd to tell tales of unconventional love, desire, and longing. Like its predecessor, To Paradise deserves a place on the mantel of esteemed genre-bending queer fiction, alongside Renee Gladman’s The Event Factory, Samuel R. Delany’s Dhalgren, and other novels engaged in radical world-building.

Review: White on White

Ayşegül Savaş’s novel White on White, published December 7th of this week, functions like a Russian doll. Throughout the story, an unnamed narrator cracks open one doll after the next for us, revealing evermore intricate renderings of her subject of observation, until we get to some—possibly crystallized—core.

Review: Dreaming of You by Melissa Lozada-Oliva

Necromancy is an art we participate in every time we hear Kurt Cobain’s guitar, the emotive neo-jazz drone of Amy Winehouse’s voice, the romantic surrender of Selena Quintanilla-Pérez’s “Como La Flor.” It is equal parts disrespect and tribute to not let the dead rest by continuing to immortalize them in art. It’s a complicated remembrance, one that raises questions about who we are in the living world, about why we love what we love, why we sing the songs we sing, why we remember who we remember.

Writing and Riding: An Interview with Adin Dobkin

In 1919, right after World War I, Tour de France cyclists united a country that had been torn apart by unprecedented desolation and tragedy. Sprinting Through No Man’s Land by Adin Dobkin explores how they did it. Told through the eyes of L’Auto editor Henri Desgrange as well as some of the cyclists that participated in the 1919 Tour de France, the book—written in chapters interspersed with photographs—guides us through the race as it describes the war-torn landscape and the people who live in it. A razor-sharp focus on the cycling narrative as dug out from archival research by Dobkin accompanied by a deft, descriptive painting of the aftermath of the Great War lends a rich, full tone to the retelling. Here, Dobkin and Shah sit down at the Hungarian Pastry Shop with some tea, coffee, and almond blondies to talk about nonfiction craft, the process of writing the book, and larger discussions surrounding sports today.

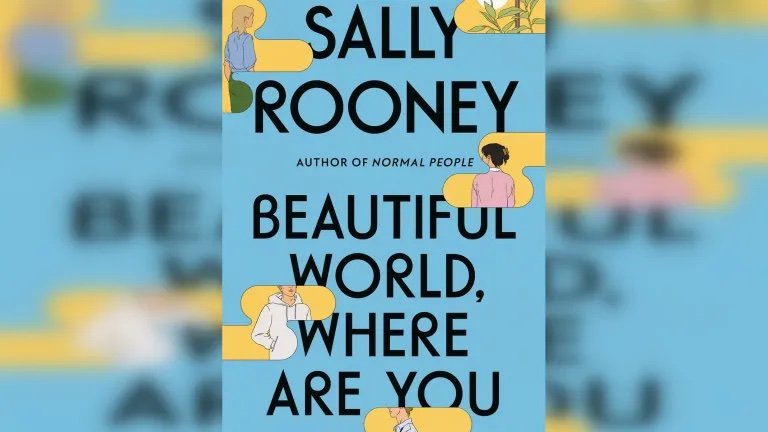

Review: Beautiful World, Where Are You

Sally Rooney is back and for sale. Her third novel, Beautiful World, Where are You, came out yesterday at the peak of a marketing campaign that seems to be more focused on distributing swag and “experiences” than getting books into hands. For an author who once said “I am very skeptical of the way in which books are marketed as commodities…almost like accessories which people can fill their homes with,” it is hard not to wonder if Rooney is living through her own personal apocalypse as bright yellow Beautiful World bucket hats are sent out to celebrities for photo ops.

A Conversation with Chessy Normile

Madeleine Cravens, M.F.A. candidate in poetry, sat down with poet Chessy Normile on a stoop in Brooklyn to talk about humor, vulnerability, and revision. Normile’s debut collection, Great Exodus, Great Wall, Great Party, was awarded the 2020 APR/Honickman First Book Prize, judged by Li-Young Lee. This book’s poems are irreverent and highly intimate, drawing the reader in through topics such as the Bible, theories of time, and trauma. As Li-Young Lee writes in the introduction, Normile’s poems are “born of an imagination that is unpredictable, fearless, probing, self-questioning, and marked by the influence of a hidden wisdom some might consider folly.”

frank: sonnets by Diane Seuss

I first opened Diane Seuss’s new collection, frank: sonnets, in Maria Hernandez Park in the Bushwick neighborhood of Brooklyn on one of the first sunny days of Spring.

The Poet as a Revolutionary Force – A Review of Cedar Sigo’s Guard the Mysteries

Guard the Mysteries (Wave Books, 2021) is a collection of five talks given by poet Cedar Sigo for the Bagley Wright Lecture Series in 2019. His scope is broad, considering everything from poetry’s potential as a revolutionary force to concepts of identity, personal and shared histories, and the life and work of poets who have been influential in his practice. But “lectures” would be too reductive of a word for what Sigo has accomplished. Each talk works in dialogue with the others, oscillating fluidly between different themes and ideas, rhythmically building towards a satisfying culmination. The lectures, presented over several months, achieve an orchestral resonance when read consecutively. Sigo touches the heart of what it means to not only be a poet, but to be living. That is not to say these talks lose themselves in abstract, ethereal concepts—they are teeming with interesting anecdotes about key figures in America’s literary and activist history, and are firmly grounded in the real world. Writers and readers alike will find this work enriching and informative.

Review: Of Women and Salt by Gabriela Garcia

From the cigar factories of 19th century Cuba to sleazy Miami nightclubs and a family detention center in Texas, Gabriela Garcia’s debut novel, Of Women and Salt, follows the lives of women fighting to survive in countries and relationships hellbent on destroying them.

Feeding the Poetic Demon with Douglas Kearney

If crossing Dionysian boundaries is true poetry, then no one makes the poetry demon swoon like Douglas Kearney does. Kearney is a star-studded poet, performer, and librettist. Accolades include a Whiting Award and fellowships from Cave Canem and the Rauschenberg Foundation. Kearney has published six collections, including Buck Studies (Fence Books, 2016), Someone Took They Tongues (Subito, 2016), and Mess and Mess and (Noemi Press 2015). His latest poetry collection, Sho (Wave Books, April 2021), provides a kaleidoscope of splintered selves and voices. In Sho, the speakers of Kearney’s poems are at once the antagonistic tricksters who enchant you (“I aspire to be a CVS: Lord”) and at once the documenters of historical and current wrongs (“Black wench! Clipped finches’/ shrill in brass lattice.”)