Feeding the Poetic Demon with Douglas Kearney

If crossing Dionysian boundaries is true poetry, then no one makes the poetry demon swoon like Douglas Kearney does. Kearney is a star-studded poet, performer, and librettist. Accolades include a Whiting Award and fellowships from Cave Canem and the Rauschenberg Foundation. Kearney has published six collections, including Buck Studies (Fence Books, 2016), Someone Took They Tongues (Subito, 2016), and Mess and Mess and (Noemi Press 2015). His latest poetry collection, Sho (Wave Books, April 2021), provides a kaleidoscope of splintered selves and voices. In Sho, the speakers of Kearney’s poems are at once the antagonistic tricksters who enchant you (“I aspire to be a CVS: Lord”) and at once the documenters of historical and current wrongs (“Black wench! Clipped finches’/ shrill in brass lattice.”)

Egghead Watch: High And Low, A Case For The Other Akira Kurosawa Film

My senior year English teacher showed me the wrong movie directed by Akira Kurosawa, Rashomon. While Rashomon, a 1950 Academy Award-winning psychological classic, may bea well-assembled masterpiece that slowly reveals itself as a meditation on perspective and ultimate truth—for an insecure 17-year-old whose favorite movie was (is) Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith, Rashomon was a dreary, one-note, strangely acted “snooze-fest” that lacked relatability to the world I was living in.

Review: Milk Fed by Melissa Broder

“She thought of people she had seen holding hands in movies, and why shouldn’t she and Carol?” This question, from Patricia Highsmith’s 1952 lesbian romance The Price of Salt, is related from the perspective of Therese, a shopgirl and aspiring set designer who has fallen in love with the wealthy, mysterious Carol. Nearly seven decades and a social revolution later, a similar question is posed in Melissa Broder’s Milk Fed, as the novel’s narrator, Rachel, sits in a Los Angeles movie theater with her love interest, Miriam. “What about holding hands in a movie theater? Can girls hold hands in a movie theater?” Rachel asks, probing, in bad faith, the strictures of Miriam’s Orthodox Jewish religion. After an agonizingly long pause, Miriam says yes, and what follows is a sequence of actions so libidinally charged that it leaves Rachel physically sick with desire.

Review: Love and Other Poems by Alex Dimitrov

So much of art, if not all of it, is about love. Every movie with their lovestruck leads. Each song’s lyrical strings stemming from the heart. It is a subject as predictable as it is inevitable, especially in poetry, an artform delineated by roses that are red and comparisons to summer days. Any attempt to avoid love, be it through loneliness, politics, or an appeal to the metaphysical, finds its way back inside a speaker, a desire. In this era of rapid innovation, where difference is valued above deference, love will always thwart our attempt to quantify the ineffable— those moments that, when experienced, leave no specific conscious impression, but instead, a sensation, a feeling that lingers with us forever.

Egghead Watch: Living with A Serious Man’s Uncertainty Principle

On November 2, on the eve of the 2020 Presidential Election, a tweet went viral. It was a picture of the electoral map, noting each state’s obtainable votes—though rather than shaded red or blue, they were all colored a light teal, overlaid with a photo of Fred Melamed from the film A Serious Man, flashing his quixotic grin. The caption read: “And the winner is…Sy Ableman???”

Review: Funeral Diva by Pamela Sneed

Pamela Sneed remembers her childhood: “Even my era did not allow me to be little innocent / A threat if I spoke up / A competitor for middle class white girls / who had the world handed to them / And resented me/you for surviving / thriving despite all the odds” (Twizzlers), living against the world who put so much on her back. In the memoir/poetry collection, Funeral Diva, Sneed offers us a glimpse into the 1980s to the world we live in now, traveling through time to a place where Black and Brown LGBTQ+ youth were growing up dealing with the AIDS crisis, police brutality, and struggling to keep communities together in spite of it all. Sneed uses her voice to bring space for the Black community, her eyes paint the image of growing up with terror at your front door and learning to absorb it and move forward.

Review: How to Survive Death and Other Inconveniences by Sue William Silverman

Sue William Silverman opens How to Survive Death and Other Inconveniences with a road trip in her gold-finned Plymouth, “cruising through life” down Route 17 as a teen, “planning to never stop.” Throughout this memoir/thematically linked essay collection, Silverman shows us that, metaphorically, she is still that restless young woman behind the wheel. Poring over an old atlas, Silverman can trace the places and episodes of her difficult past to map the urgency and central drive of the book: what explains the narrator’s life-long fear and obsession with death, and what does it mean to survive?

Review: The Malevolent Volume by Justin Phillip Reed

In his new collection, The Malevolent Volume, 2018 National Book Award, and Lamba Literary Award Winner, Justin Phillip Reed, delves into the underbelly of identity, poetry, religion, myths through the lens of a queer, Black American. A constant theme of The Malevolent Volume is man transforming into a monster, either classically mythic like a Gorgon, or a newly invented creature. In this collection, Reed accepts and moves deftly through anger, cultural truths, contemporary references, and never turns away.

Not Your Typical Gap Year: An Interview With Pam Mandel

Rachel Rueckert, nonfiction MFA candidate, spoke to travel writer Pam Mandel about her career path and recently released book, The Same River Twice: A Memoir of Dirtbag Backpackers, Bomb Shelters, and Bad Travel, a coming-of-age story about an unconventional, emotionally fraught gap year at home and abroad. With no guidance or concrete plan, Mandel embarks on a tangled journey across three continents, from a cold water London flat to rural Pakistan, from the Nile River Delta to the snowy peaks of Ladakh and finally, back home to California, determined to shape a life that is truly hers.

Review: Luster by Raven Leilani

“I was happy to be included in something, even if it was a mostly one-sided conversation with a man twice my age.”

On Intersectional Character Dynamics & Subverting their Tropes: An Interview with Jenny Bhatt

Shalvi J Shah, an MFA candidate in Fiction and Literary Translation and Teaching Fellow at Columbia University, talks to author Jenny Bhatt about craft, cultural stereotypes, her debut short story collection Each of Us Killers, and how far artists go to create.

Literary Citizenry: A Podcast Interview with Publisher and Poet Joe Pan

Columbia Journal is excited to introduce our podcast with poet Joe Pan, publisher of Brooklyn Arts Press and the smallest press to ever win the National Book Awards. Hear the episode, which details a conversation between Columbia Journal’s Issue 58 editors Shalvi Shah and Emma Ginader. Find out what it means to be a good literary citizen, how longing and anguish can create space for civic or literary engagement, and the perils and joys of small press publishing in this riveting interview with one of the literary world’s visionaries.

Review: Girlhood by Melissa Febos

How do you heal from the pain of growing up? This question, refracted through a feminist lens, lies at the heart of Melissa Febos’s essay collection, Girlhood. With psychological clarity and emotional precision, Febos revisits the past to rewrite the future.

Review: The Lightness by Emily Temple

I felt many things as I read The Lightness, which is probably why I’m typing out this review a mere six hours after putting down the book. Generally, I’d let a book marinate. I’d let my mind soak in the words, the narrative, and the pages. Normally, I’d emerge slowly from the world of fiction, reluctantly type out a review, and then return to a world that’s achingly real. But with this book, I have mixed feelings. Feelings that I may forget if I soak for too long. So I’m emerging from the pages and deep-diving into my brain here.

Review: Life of the Party by Tea Hacic-Vlahovic

An elaborate disappearing act, Tea Hacic-Vlahovic’s novel Life of the Party (Clash Books) plots a young woman’s debaucherous romp through Milan’s high society as she acclimates her existing problems to a new milieu saturated by the fashion world and its attendant vices.

Review: Friends and Strangers by J. Courtney Sullivan

Familiar facets of our modern existence—the kinds of things that trend on Twitter—loom large in Friends and Strangers, the fifth novel from J. Courtney Sullivan, out this summer from Knopf. It follows Elisabeth, a New York writer displaced in the suburbs with her husband and newborn son, and Sam, a college student Elisabeth hires as a babysitter. Swirling around them are such attractions as a student rally against unequal pay for university workers, tiffs and tussles within a popular mommy Facebook blog, a social influencer chasing bikini-brand deals, and a book idea decrying the loss of the American identity. It’s a novel that reminds you just how hyper-aware the world has become since, say, the early 2010s—the war between genders, races, classes—and yet never loses sight of its timeless keystone: the strength of the bonds built by women, between women. This, coupled with the trials of stale love, and a fair few lies and secrets, comes together in a story that, at the heart of its 400-something pages, chips away at the stunning intimacy we can sometimes share with strangers.

Review: The Sprawl by Jason Diamond

In The Sprawl: Reconsidering the Weird American Suburbs, writer and journalist Jason Diamond, author of the memoir Searching for John Hughes, returns to the suburbs of his childhood and adolescence in an attempt to better understand their impact on American culture. From a distance of time and space, Diamond considers the suburb as both concept and place, an in-between defined in relation to the urban center—a place which, linguistically if not physically, lies “beneath” the city. Diamond’s gaze, astute and compelling, is critical not only of the object of its inquiry but also of itself—of the hesitant, intricate love we have for the places that shaped us.

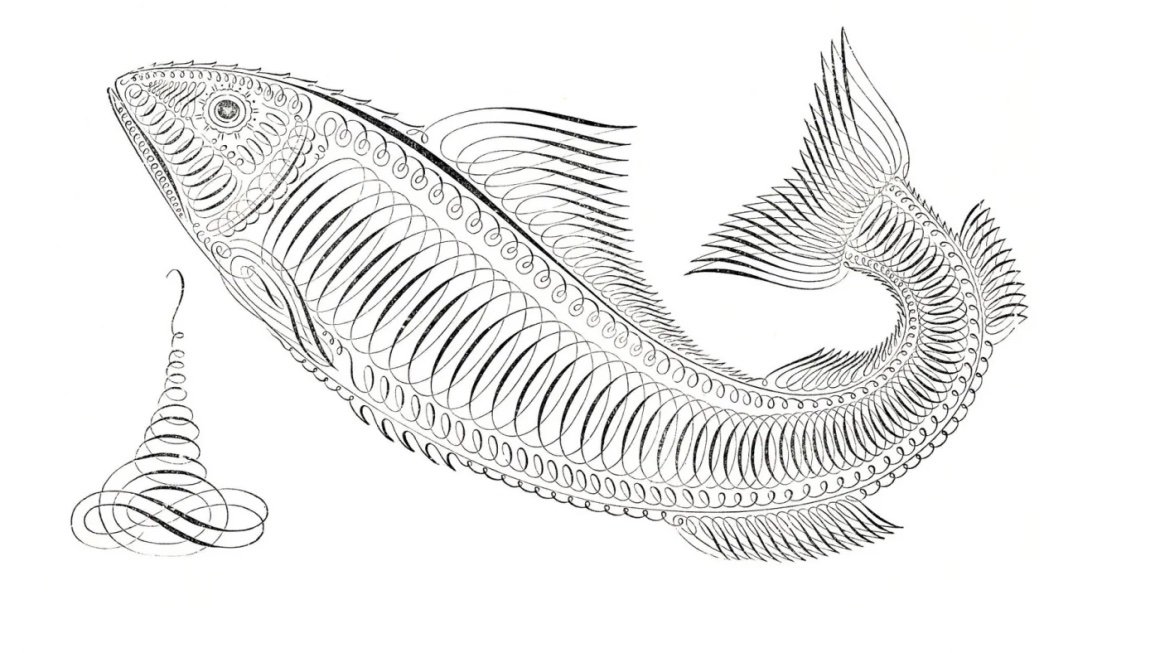

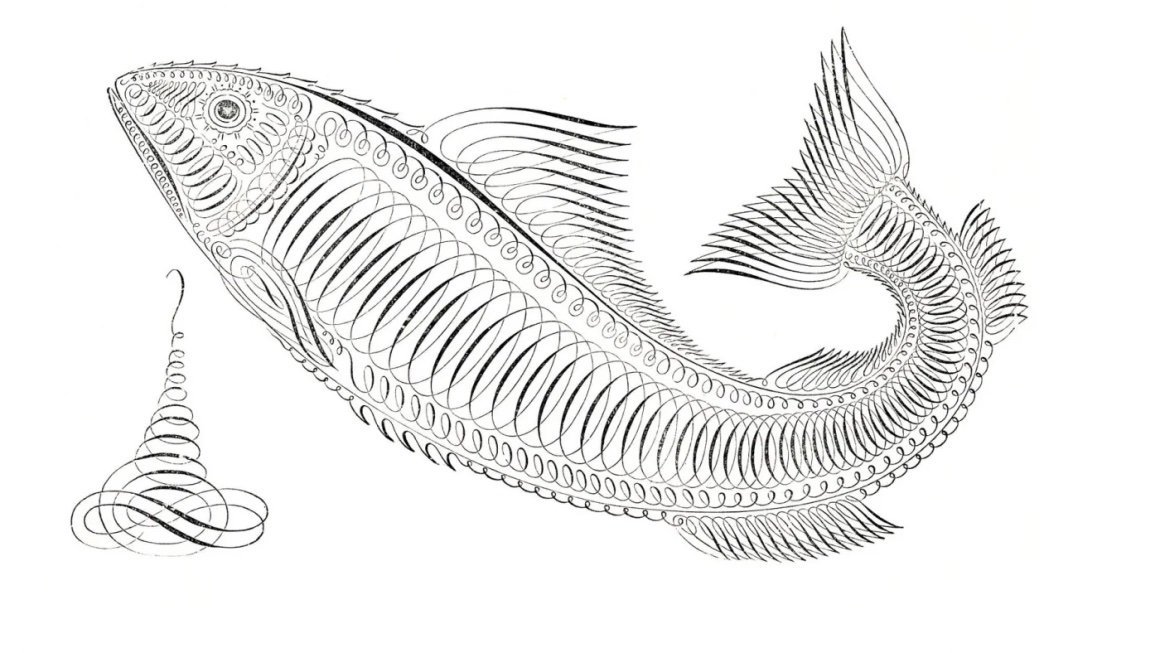

Review: World of Wonders by Aimee Nezhukumatathil

If ever there were a season that needs a do-over, it’s summer 2020. The most expansive and languid of seasons has become stilted and bowed under the pandemic restrictions. There’s the enforced indoor time, the constant bad news, and the de rigueur doom scrolling to take in everything. Into this summer of our discontent comes poet Aimee Nezhukumatathil’s first book of essays World of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, and Other Astonishments. Here is everything that’s been missing: family, food, travel, immersion in nature, the abundance of the season, the time to slow down and savor. There’s so much to be dazzled by in the world, Nezhukumatathil reminds us. Pay attention.

Review: Being Lolita by Alisson Wood

Coy best describes Alisson Wood’s relationship with the reader in Being Lolita. Wood cunningly uses the reader’s knowledge so that, at decisive points, they either read with or against the grain of this text. In the preface, Wood narrates her and the teacher’s first kiss. When the teacher kisses the inside of Alisson’s ankle to quell the itch of a mosquito bite, Alisson hadn’t read the novel. At that point, Mr. Nick North, her English teacher, told Alison that the story of Humbert and Lolita is a love story. A reader’s reaction to her admission sets up their relationship with the rest of the memoir. If you know anything about Vladimir Nabokov, you know what Lolita is about.

Review: Antiemetic for Homesickness by Romalyn Ante

Romalyn Ante’s debut poetry collection ‘Antiemetic for Homesickness’ illustrates that longing, desire, and need for home. In the poem ‘Memory’, Ante’s speaker uses Tagalog to demonstrate the undeniable claim in longing for a place that is now absent in one’s life. ‘Tahanan means Home, Tahan na means Don’t cry anymore’. Each poem in Romalyn Ante’s book helps navigate the journey in moving from one home and creating another. The poems teeter on the language of two different perspectives, one from birth, which was the Philippines, and one of bombardment that was the United Kingdom, where she now resides. The poems move between English and Tagalog, which speak to Ante’s experience, navigating her own culture and that of the culture she has to present in. There is the Westernized Gaze glaring at Ante, and these poems speak to that fight against assimilation and succumbing to it. Ante’s book also speaks to the people who are left behind in search of a better life. One only has their memories to keep their hope and drive alive to find better opportunities as an immigrant. In the poem, ‘Only Distance’, Ante’s speaker recalls a memory, “When all the stars are out, she returns/ to this tropical wind, to the constellation/ of moles on his shoulder, his second-hand clothes./ He slices mangoes, and lays them on a banana leaf./ She’s with him…”