Diagramming Desert Ecstasy: Notes on Confetti

By Emmalea Russo

The diagrams below are excerpted from Emmalea Russo’s new book of poetry, Confetti (Hyperidean Press, 2022).

Confetti begins and ends with ecstatic sunrises/sunsets in the 1970s, opening with The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) and closing with Zabriskie Point (1970). At the end of these films, just before the credits roll, sun follows violence. Leatherface swings his famous chainsaw through the air as Sally just barely escapes, sun coming up behind him, sunspots blotting out the horizon. Zabriskie Point ends after a house in the desert explodes in a scene that was shot with 17 cameras as objects come apart and get abstract in confetti-like blasts: Wonder Bread, refrigerators, TVs, meat, clothes. It’s a cathartic and bizarre hallucination, a dream sequence in slow motion which gives way to new light. Antonioni said he chose to shoot Zabriskie Point in Death Valley because it’s “so beautiful and not because it’s dead.” He also said: “It’s not a question of reading between the lines, but one of reading between the images,” an idea which also guides Confetti.

Confetti, Emmalea Russo, Hyperidean Press, 2022.

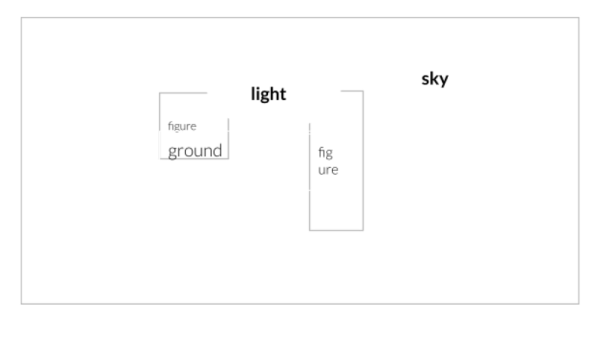

In addition to poems and prose, Confetti contains sixteen screen-shaped diagrams/drawings which I made from paused moments in various grindhouse and arthouse movies, both “high” and “low.” Except for Claire Denis’s Trouble Every Day and Bruno Dumont’s Twentynine Palms, both from the early 2000s, I largely chose films from the late 1960s through the late 1970s (the eve of the digital): Teorema (1968), Zabriskie Point (1970), I Clowns (1971), The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), House (1977), Les mains negatives (1978), and Hellraiser 2 (1988). The diagrams are not informational so much as playful attempts to see and read differently, to locate geometries while also following those extreme highs and lows (love, horror, bright light, weird fluids…) that trouble form and frame with their aberrant movements. In Life-Destroying Diagrams, Eugenie Brinkema writes: “Violence compels a slow, deep attention to the details of design–what cannot be paraphrased or summarized, but must instead be read–and a formal disposition is not an evasion of the world’s working, but the basal requirement for persisting in the world a slight bit longer.”

Confetti has seven sections and the diagrams compiled here are from the final section which is “set” in the desert, a zone I think of as both pre- and post-cinema where forms come apart and wed in odd and mirage-like plays of light. A site of mystical illumination and terror, a screen of excess sun. In America, a text I was thinking a lot about when writing this section, Jean Baudrillard says that the desert contains the “foreshortening effects of cinema.” Two films appear in this section, both shot in the deserts of California by European directors: Zabriskie Point (1970) and Twentynine Palms (2003) where sun seems to prophesy violence and/or ecstatic fusion while also pointing to cinema as a medium of light. There are wide and God’s eye shots that feel both awe-inspiring and paranoia-inducing, a weirdly wired air buzzing with surveillance and freedom as seen through the eyes of outsiders. In the two moments I draw in the book (shown below), lovers stare into light and get blotted out, revealing how the exposed eye/I might get dissolved, overwhelmed, and dazzled. Bodies fuse with screens, light, and other bodies. “Love is not consolation,” wrote Simone Weil, “it is light.”

Confetti, Emmalea Russo, Hyperidean Press, 2022.

I think of the diagrams as frame-like floating vessels, alchemical and kind of funny. They diffuse into the surrounding zones. I was thinking about the disorienting transition from analog to digital. I was thinking about Hollywood, a zone which disperses as the screen stretches. If film is what happens between frames in movements our eyes can’t perceive, than the poems in Confetti are like film in that they happen between–between finding something and somewhere in what might appear to be nothing and nowhere. Michelangelo Antonioni said: “Hollywood is like being nowhere and talking to nobody about nothing.” But I guess Confetti finds sustenance in the apparently noncaloric. There’s mysticism, soda water, fear, weird white light, trash, and sugar. But writing about the book now that it’s finished is trippy, like maybe I’m not supposed to be doing it. Nothing much more to say. Simone Weil: “The divine emptiness, fuller than fullness, has come to inhabit us.”

About the Author

Emmalea Russo‘s poems and writings on film and visual art have appeared in many venues, including Artforum, BOMB, and Granta. She is the author of G (Futurepoem, 2018), Wave Archive (Book*hug, 2019), and Confetti (Hyperidean, 2022).