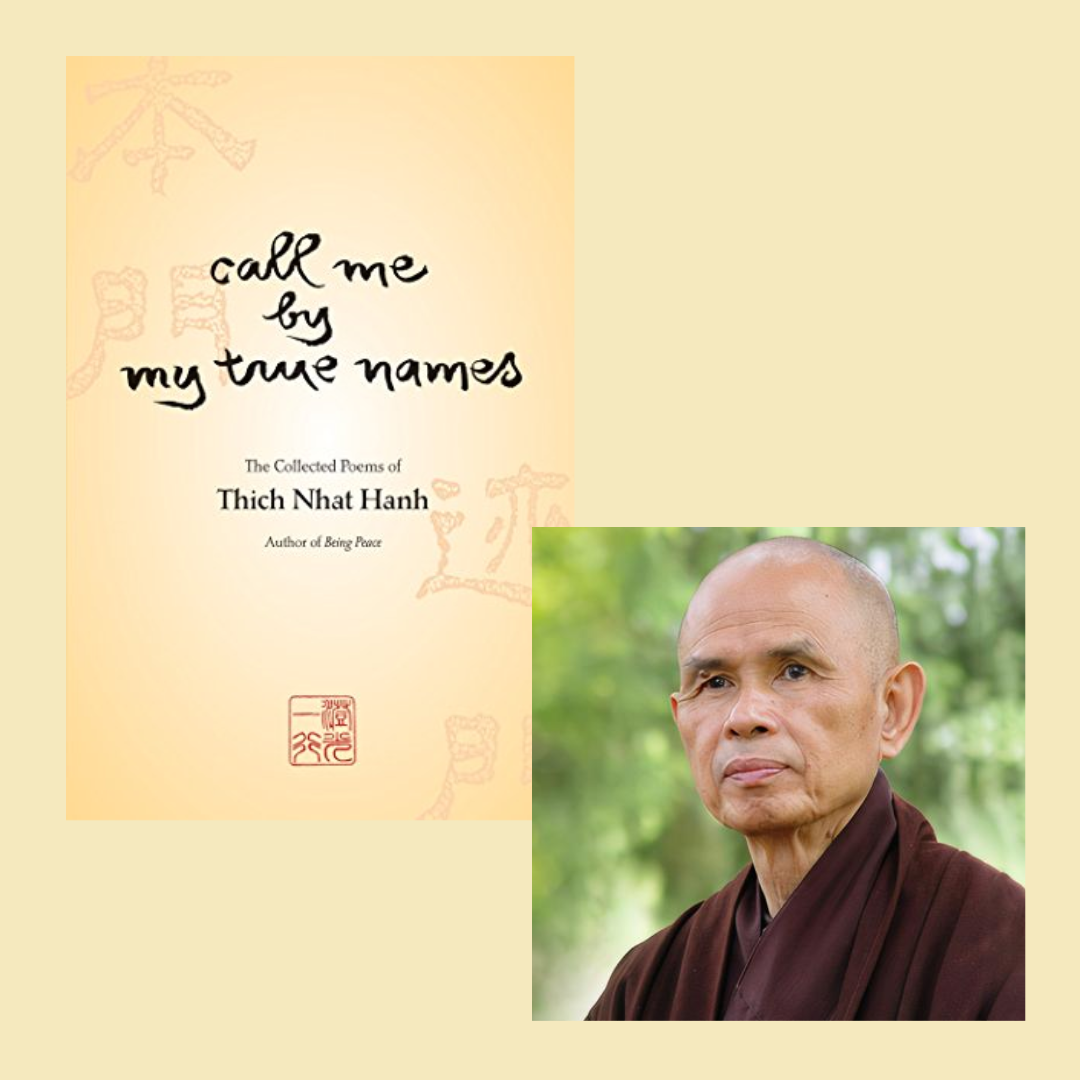

Call Me By My True Names – the Collected Poems of Thich Nhat Hanh

By Linh Luu-Hopson

A Review of the Monk’s Work, Teachings, and Legacy 1 Year After His Death

Known for his teachings on Buddhism and how to bring mindfulness—the idea of being aware of one’s thoughts, actions and emotions in every-day life—Thich Nhat Hanh is a name many students on the path to enlightenment are familiar with. Until his passing at the age of 95 in early 2022, Thay (how Thich is often referred to by his students, Vietnamese for “teacher”) has published more than 100 books encouraging people from all faiths to incorporate Buddhist teaching in their daily lives, with millions of copies sold in the U.S. alone.

Unlike many of his more philosophical or teaching books (his “How to” series comes to mind—How to Eat/Fight/Love/Relax/Sit), Thich Nhat Hanh’s final poetry collection, Call Me by My True Names is unique because of its message of merging the spiritual with the non-spiritual realms. Published in a second edition in 2022 (the first edition was published in 1999), the collection explores the long life of a spiritual teacher and healer. It spans his early days as a monk witnessing the grief of the Vietnam war to his decades-long career promoting peace and non-violence to world leaders and readers across the globe.

Thay’s spiritual books are geared towards understanding how to liberate oneself from suffering through mindfulness. His poetry gives us a front seat to the very real and intimate suffering felt by the Vietnamese people during the war. “Who will be left to celebrate a victory made of blood and fire?” (from “The Sadness of War”). Buddhism is based on the belief that suffering is a part of life—they are taught to embrace negative emotions and stay introspective about their natural plight. Yet in this poem, Thay suggests that spiritual teachers, including monks, must speak up about them in order to heal the root cause of the wound. “My soul is leaving me/ In anger,” he writes. Thay stood out by encouraging monks to respond directly to war and violence rather than stay neutral. About “The Sadness of War,” Thay writes that he was inspired to respond to a comment made by an American military man that he had overheard say, “We had to destroy the town in order to save it.”

In “Mudra,” a hand gesture used by monks to symbolize devotion and prayer, Thay merges spirituality with grief. “Don’t listen to the poet./ In his morning coffee, there is a teardrop […] “my hand will never turn over on this table/ like the half-shell/ balancing on the shore,/ like the corpse of a man struck down by a bullet.” The juxtaposition of Mudra and suffering from war echoes Thay’s concept of “engaged Buddhism”—a concept that he coined to define the use of Buddhism to support humanistic values, one that influenced leaders such as Martin Luther King, Jr. and marked his refusal to take sides in the Vietnam War. In 1967, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. nominated Thay for the Nobel Peace Prize. King acknowledged Thay’s influence on peace movements in the States as well as Vietnam.

Thich Nhat Hanh’s poetry reveals more than a monk on the path to be a globally respected teacher of peace and non-violence; he is a man with emotions and desires. In “The Beauty of Spring Blocks My Way,” Thay shares an intimate poem he wrote “less than twelve hours after [he] fell in love with a nun.” Both Thay and the nun realized that they could not be both in a romantic union and pursue their spiritual calling. Forgoing his romantic desires was not an easy process, and Thay described in detail the pain of that decision. “I suffer so. My soul is frozen./ My heart vibrates like the fragile string of a lute.” Monks do not talk openly about their memories of physical desires, yet Thay did in this poem about his love for the nun. Through his poetry, Thay teaches that spirituality and individualism can co-exist. As a Vietnamese person myself, I find it surprising that this eastern concept of Buddhism and devoting one’s life to others can coexist with one’s individual needs and emotions.

Through the story of a brother returning from shipwreck in a poem titled “I Will Way I Want It All,” Thay expresses that suffering is not to be feared because it can bring about the total transformation of one’s identity, free from limitations. In the story, a monk sets fire to the shelter of a sailor returning home from a shipwreck. The act of destruction, rather than a curse, is a blessing. The monk is helping his brother let go of his attachment to material things. “One night, I will come/ and set fire to his shelter, the small cottage on the hill […] In the utmost anguish of [the brother’s ] soul,/ the shell will break./The light of the burning hut will witness/ his glorious deliverance.”

The destruction of material things incites an emotional breakdown and release in the brother, reminding him of the possibility of a new life. By pushing the brother to not attach himself to material things, the monk encourages him to seek true spiritual growth. The last line of the poem cryptically suggests the idea that the most powerful journey is not the physical one, the literal journey in the sea, but the journey of one’s soul: “I will be there to contemplate [the sailor’s] new being”/ “he will smile and say that he wants it all—just like I did.” Instead of wanting to go to more places or do more outward actions, if one stays courageous enough to face one’s inner qualms, he will be able to “smile” instead of being deterred by a trauma like a shipwreck. Thay suggests that the ordinary person seeking total reinvention through spiritual enlightenment will have to endure the “burning down” of his past material life. At first, I was quite shocked by the image of a monk setting fire to anything, let alone a man’s home. It was this sense of pushing one’s expectations of what a monk does or doesn’t do that makes Thay’s poetry so unordinary.

Thay passed away January 22, 2022 at Tu Hieu Temple in the city of Hue, Vietnam, where he was born. At the height of the Vietnam War, he was criticized on every side for his anti-war stance. The anti-war poem that led to his exile from Vietnam, “Condemnation,” is included in Call Me By My True Names. “Whoever is listening, be my witness:/ I cannot accept this war./ I never could, I never will./ I must say this a thousand times before I am killed.” His exile officially ended in 2015 because the government intended to support a globally respected peace leader and spiritual teacher. In 2018, Thay moved to Hue, Vietnam, after 39 years of exile, back to the temple where he had once studied as a youth. The sadness from his many years of exile is often recalled in his poetry. The passing of Thay in his home country marked the homecoming for one of its nation’s most courageous leaders. To honor Thay’s death, one would be wise to remember his poetry on acceptance and living in union with all people. “Brothers and sisters/ the beautiful Earth is us,” “Let us accept ourselves/ so we may accept one another./ Let us share the vision and make it possible/ for Great Love to arise.”