Labyrinths

By Arya Samuelson

Labyrinth as Medical Drama

My mother speaks for me. I nod along as she recounts the twisted history of my illness, too weak to correct her when she trips over a detail. “I’m a doctor,” she declares, and physicians pay heed. They answer her litany of questions, tolerate the shrill panic in her voice. My mother is a medical professional, and this is my golden ticket—the only thing that will save me. I’m one of the lucky ones. Some people wait years, decades, hundreds of thousands of dollars before they arrive at a diagnosis of Lyme Disease. Mine came easy: a week after the pink rashes that colonized my skin, a variant of the classic bull’s eye. Treatment was supposed to last four weeks.

Throughout my senior year of high school, my mother shuttles me to doctors’ visits. Getting out of bed is near-impossible; when I do, my brain is a tangle of strings. Strings that turn to dumb bricks that fall at my feet. I cry at everything—studying for a test, thumbing through clothing that doesn’t fit, choosing a cereal, every time someone’s short with me, or kinder than I deserve.

My mother is always there, cooking, cleaning, coaxing, consoling. She coaches me through college applications and convinces the principal to let me graduate on time, despite failing everything—even AP Art. She arrives at the meeting with frantic, half-curled hair and appeals to pity. “Can’t you see how sick she is? She’s always been a top student, now you’re going to punish her by making her repeat high school?” I sink into the pockets of my ripped sweatpants, dissolve into deep quiet shame. My teachers are quick to concede, but fear radiates as I imagine the next years of my life home-bound: Will there ever be a time when I won’t have to depend on my mother?

The doctors implant a central venous catheter in my chest, a port where they can thread IV antibiotics through the largest vein in my body, a couple inches from my left breast. The nurses promise I’ll find a prom dress that will hide the bulging needle. They prick me beneath interrogatory fluorescence, just above my heart.

But a day later I’m back at the hospital. My chest is spasming – the motion like the word itself, the m so fast it’s a mistake, an involuntary tensing. My body is a ferris wheel of pain, contracting, spreading, winding around itself. When a nurse finally probes at me, she concludes that everything looks right. I writhe animal on the bed.

Nothing is wrong. Words I’ve waited my whole life to believe. I’ve always wished my mother would tell me everything was okay, that emotions were like floating clouds. No need to worry. But my body knows these reassuring words are no truer than they’ve ever been.Something is definitely wrong. The physician splashes around word soup. Nurses urge me to be patient.

The next day we’re back again, the pain in no way abated.

My mom calls my dad who drives an hour and a half, determined to play the good guy. His chirping girlfriend arrives beside him. She’s a doctor too, but the kind who delights in small talk with nurses, asks about my college apps, and reassures me in a sparrow’s high-pitched voice: all of this will be over soon. Meanwhile, my dad dazes out, flips channels. My mother waves around her golden ticket, her eyes wild and black. The nurses roll their eyes and deliver half-baked excuses for the doctors. As she yells and threatens, her nipples protrude pointy arrows through her shirt. She has crossed a line, no longer a professional, only a mother again. The girlfriend tosses my dad a horrified glance when she thinks I’m not looking. I cling to the scratchy hospital bed, clutch at the abrasive sheet paper. My mother is the only one I trust.

The doctor yanks out the needle. “How do you feel?” he asks with a corny grin. All my language has been drained. My dad leaves with his girlfriend. My mother drives us home and I can’t stop fingering that pink burst of skin.

In a medical drama, a brilliant, often sociopathic doctor comes to the rescue and uncovers the truth of the patient’s illness. The center of a labyrinth, the story at its core. Ten years later, the scar on my chest is a tiny button. A knot in a tapestry you can only feel with your fingers.

Ten years and I’m still waiting for answers. Every story is so faint, a tender upturn of skin.

Labyrinth as Ferris Bueller’s Day Off

At nine years old, there’s no need to jam a thermometer under my tongue or cough my voice raspy. My mother always believes me. All I do is clutch at my stomach and tell her I’m too sick for school, and she hands me a bottle of Pepto Bismol that tingles my throat pink and warm. I’d drink a hundred bottles if I could.

By the time I’m eight, we’ve moved every two years of my life. At each school, I charmed teachers and peers with my passion for keeping track of birthdays, nicknames, pets, anything that could be turned into a list. But at my new school, all the kids have known each other since kindergarten. Joining in third grade is like making changes to a book that’s already been printed: you can only write in the margins. My third-grade teacher places me next to a girl named Arielle because she thinks we’ll like each other. Instead the teacher calls us by the wrong names all year. Arielle cringes whenever “Ariana” is called and the other kids laugh.

It’s the first time we’ve owned a house. It’s the first time I wished we would move and start over again.

No school means my mother stays home, swaddles me with blankets, and cooks chicken soup that simmers through the afternoon. We drink peppermint tea and eat steaming bowls of rice with butter while watching movies from the list of 100 Best American Films. Together is safe. Together is home.

“I’m still sick,” I whine the next morning, trying to contain my excitement. She believes me, but she has to work. “You’re abandoning me!” I scream. I hate her patients, those needy siblings I’ve never had, always clamoring for her attention, calling her cellphone all day and night.

“I’m sorry.” Her eyes glitter with guilt.

She clutches at the doorknob. Hesitates.

“You should be,” I say.

As the door slams, I collapse onto the sofa in remorse.

Without her, the house feels suffocating and empty at the same time. I flip through a couple of books or watch one of the movies on the list The Three Colors Trilogy or Seven Samurai – but they’re too abstract to follow. I watch Disney Channel reruns about middle school misfits, but they remind me too much of myself. I scour the freezer and pull out boxes of Trader Joe’s meals. Wontons by Trader Wong’s. The microwave hums and spins. I rip open another package. Steamed dumplings. Spanokopita. Meatballs.

I learn to forge her signature—a furious scrawl of letters—so I can come home anytime I want.

Labyrinth as Living Room Sofa

After a hard day, a disappointing encounter, a stormy evening, to the couch we go. My mother traces the soft ridges of my feet, snips at my scraggled toenails. I sip peppermint tea and we start digging. Why am I so sad? So insecure? So anxious? She listens, helps shovel the dirt. The core layer is my father—how he didn’t protect me from my stepmom’s abuse—yet, somehow, there is always more. I draw my name with shifting suede textures: a warbled mess. We dig for hours. As a psychiatrist, my mother believes uncovering this core truth will set me free, but every time we think we’ve reached something solid, it’s just another clump of dirt and I feel powerless, ugly, and unspeakably sad. But we stay on the sofa, her rubbing my feet and picking at my scabs until we’ve exhausted all words. Until we’ve created a labyrinth as deep as it is wide. We rest our shovels against the sofa cushions. There’s always tomorrow.

Labyrinth as Namesake

My birth name is Ariana, derived from the Greek name Ariadne.

In Greek mythology, Ariadne is the princess of Crete. Her father, King Minos, constructs a labyrinth to contain the Minotaur, a monstrous bull-headed creature who also happens to be his wife’s son—a punishment inflicted by Poseidon onto Minos for coveting his finest bull. While the construction of the Labyrinth is underway, King Minos discovers that his only human son, Androgeos, has been killed. Though sources dispute the cause of Androgeos’ death, King Minos blames the Athenians for the destruction of his family line. As vengeance, King Minos orders seven men and women from Athens every year to be chosen as human sacrifices for the Minotaur.

The Prince of Athens, Theseus, is determined to defend his country and volunteers for the slaughter. Ariadne falls in love with Theseus at first sight. Though she cannot protect him from entering the labyrinth, she gifts him a special sword and a ball of yarn. This way, he can defeat the Minotaur, trace his steps, and return to her. Ariadne understands, as perhaps women always have, that winning is only the half the battle. You have to find your way back home.

With the help of these gifts, Theseus defeats the minotaur and escapes. Fearing retribution from Ariadne’s father, the two elope by sea.

Ariadne’s story has always captivated me, especially its tragic ending: Theseus abandons her on a remote island and sails away. In some versions, she marries Dionysius, the god of wine. In others, she hangs herself. Neither seemed to me a suitable fate for a princess whose love was so strong she fled everything she’d ever known and whose gifts defeated the Minotaur, ending the cycle of violence in her country. In every version of the story, it’s Ariadne’s ball of yarn—a woman’s gift if there ever was one—that is responsible for Theseus’ victory. Yet she is the one punished. Perhaps she loved Dionysus, but I could never believe it. Ariadne was a scorned woman, stranded in the middle of the sea, and Dionysus the god of hedonism. The Greeks were never known for practicing consent.

At thirteen, I wrote a poem about her: Ariadne, you gave me your name / but was your sorrow included? Already I feared the salty waters of sorrow would stay more familiar than the pleasures of wine.

Labyrinth as Escape (Fantasy)

I walk out of class into the cool, indifferent rain. Rain that doesn’t care enough to pour, only to dampen my denim with a mossy smell, cling to me with cold fingers, ensure my curly hair always looks like shit. Nobody uses an umbrella in the Pacific Northwest. It’s sophomore year of college and I’ve become as drab as the dark sky, hidden as the withholding sun. My classmates—the ones I sit next to every day, exchange laughs with—walk by without a nod of acknowledgment.

Thank god I’m getting out of here. Remembering my secret, excitement confettis through me. From my constant moving as a kid, I learned that leaving was always a possibility. But once it was an option forced on me. Now it’s a choice I can make for myself.

Back in my dorm room, fingers trembling, I dial my mother’s number on Skype.

“I was just thinking about you!” Her voice reaches out to me through the thick fog of rain like the start of my favorite song. Her image peers back at me, a near-reflection of my own. People always comment on how similar we look, and they’re right: we both twist our dark frizzy hair when we’re nervous, mix up idioms right and left, and fling our hands in despair. It’s also true that sometimes when I look at her, I lose all sense of myself: what I want, what I don’t, who I am.

“Aren’t you always?”

“No…” she smiles coyly.

This is our routine. Each time she tells me this, and I dare her to admit there’s a moment when she’s not thinking of me, when we’re not connected.

“How are you?” she asks.

“Um, I’m pretty good.”

She cocks her head and I can read her thoughts. I’m never “pretty good.” At least, that’s never the end of the story.

“I want to hear how you are, Mom.”

Her eyes flicker with doubt. She twirls a strand of hair. “So, I have a patient,” she begins, which is how she starts most stories about herself. It will be some awful, impossible puzzle. Someone else’s labyrinth. I wrinkle my face in empathy. Tune out.

“So I have something to tell you,” I interrupt.

“Uh oh.” Her lips spread into a half smile, but only half-teasing.

I cling to the desk, blurt out. “Why do you always assume it’s bad news?”

“Just tell me,” she says, an edge in her voice.

“Well…” I fix my eyes just beyond her image. “I’ve decided I want to take a leave of absence from college and backpack through South America.”

Her cheekbones lift as if preparing for flight. Then everything deflates, darkens.

“Mom?”

“I mean, do you want my honest answer?” Her voice is slick as black ice. No way to skate without crashing.

“No – I just want you to support me.”

“But I can’t lie to you.”

“Why not?”

“Because then I wouldn’t be your mother. I can’t tell you I approve or support something I don’t.”

“Just this once?”

“I think it’s a terrible idea…. You have to finish college. You really think that running away to South America is going to solve anything? Without a plan, without anyone else? I think that’s an utter fantasy, Ariana.”

I scream at her. “You never want to do anything, go anywhere! The furthest from New York you’ve ever lived is Boston. You always want me to do the safe, conventional thing. Why should I trust anything you say?”

She hangs up, or I do, surrendering to the comforter of dead feathers. Rain drums at my temples. She always thinks she knows better than I do. Maybe she’s my Minotaur, the one who needs to be conquered. Maybe that’s the only way I’ll hear my own voice.

But she knows me better than anyone ever has—ever will. I fall asleep, twisting around the labyrinth.

Labyrinth as Hair Cut

At twenty, I change my name from “Ariana” to “Arya.” The idea comes to me while studying and lights my body like a chord of music. “Ariana” reminds me of the past, of roll call attendance in elementary school. The name has awkwardly long hair. “Arya” has a flourish, a bob. I’ve called myself Arya ever since and so has everyone else in my life, except my mother. She has only ever called me Ariana.

Labyrinth as Autoimmune Disease

Lyme Disease is an autoimmune disease, which means my immune system can’t distinguish between foreign cells—like viruses or bacteria—and my own. It detects itself as the enemy, releasing autoantibodies that attack my healthy cells. Thryoid. Brain. Gut. My body is a mirror at war with itself.

My parents separated when I was ten weeks old and I grew up split between households. There was my mom’s house, my dad’s house, my mom’s house, my dad’s house, which eventually became my dad and stepmother’s house. There wasn’t even Mom, or Dad, only “my mom,” “my dad,” because I was the only branch that united them. There was never simply home.

“What’s the word for when you feel two things at once? Like when I want to be with you and I also want to see Daddy and Molly?” I asked my mom at six years old as we turned the corner onto my dad and stepmom’s street. The corner bodega boasting “Sugar Mart” in huge capital letters prickled with excitement and dread, the sign we were close to the parting.

“Ambivalent,” she said.

The word crumbled on my tongue. I tried it out on my lips and it tattooed the roof of my mouth, sweet and sickly as sugar. A taste that has never left me.

Labyrinth as The Cure

When I’m twenty-five, my mother convinces me to visit a naturopathic doctor to make sure I’m free of Lyme Disease.

“But I feel great now,” I insist, knowing this isn’t entirely true. My abdomen sears with pain every morning, and I oscillate between calm and overwhelmed in a matter of seconds. But I’m used to this now.

“Please just check it out, she pleads. “For me.”

The no-nonsense doctor determines that my thyroid is severely suppressed. “People with numbers as low as yours feel like they’ve been hit by a truck,” he tells me, and prescribes a yellow bottle simply labeled “Thyroid.” Noticing the question mark on my face, he adds, “It’s sheep bovine gland from New Zealand,” and shoos me out of his office.

One month of supplements later, I feel like Dorothy when her world explodes into color and she realizes she’s been living in black and white. My abdominal pain disappears, and I rise each morning with glee. The megaphone in my brain that loudly broadcasted my deficiencies suddenly turns quiet. I flirt with strangers, initiate conversations on the subway, eat whatever I want. All this time, my problems had been curable, easily remedied by sheep thyroid from the other side of the globe.

But two months later, the golden light has dissipated. All I want to do is sleep and eat; I’m always tired, always hungry. My doctor’s description finally resonates. Every thought, decision, movement carries resistance, like weights tied around my ankles. I stay at my mother’s house for weeks, but no amount of chicken soup or peppermint tea can quell the poison inside me. The smallest task shatters me. My mother straps me into the car with blankets and pillows and we drive to a renowned Lyme Disease clinic, where they inject me with needles as large as my fingers and conduct seventy-two types of blood work. The researcher asks me to repeat back lists of words, numbers, animals to test my cognitive functions. By the time she’s finished listing, I’ve forgotten the question.

During the psychosocial evaluation, my mother waits outside. “We have all the time you need,” the doctor assures me. “Tell me everything.” Most physicians have only cared about select pieces of my history, so I’m both surprised and too exhausted to hold back. I tell the doctor about my divorced parents, my vindictive stepmother, how often I was put in the middle. How college was a blur. How I want to be a writer, but now I can barely formulate a sentence. She nods attentively as I meander through a tour of my life. My body softens, grateful my mother isn’t there to interject, re-route. For once, my voice is at the center.

When the results come back six weeks later, the doctor tells me that I am positive for Lyme Disease. But she doesn’t believe I have an active infection. Once you’ve had Lyme Disease, you’ll always test positive. Instead, she recommends antidepressants.

“But I’m not depressed,” I protest.

“You scored 10/10 on all the surveys.”

“Yes, but that’s not the root cause. Depression is just a symptom. I told you that.”

She inhales and exhales loudly. “Based on your results, I can’t determine what the root cause is. There are some things we just can’t know. But why don’t you try antidepressants and see if they help?”

Her words jab me in the chest. They puncture my button scar and twist it open. Nobody’s listening. For a few weeks, I’d glimpsed a new kind of life: Dorothy’s world of rainbows and technicolor. I don’t want to put a mask over my symptoms. I want that golden light back.

My mother immediately researches other Lyme doctors. There’s a clinic in Colorado, a specialist in Canada. She is chasing an awful diagnosis. Lyme Disease is not good news. Neither is the absence of any.

But as more time passes, I forget what I’m chasing. Maybe this is my brain, my body, my process. Maybe sadness is just part of who I am, the color of my thoughts, the flavor of my water. Every day my strength drains. How much of this is changeable? How much is just me—who I’ll always be?

Labyrinth as Ancestral Wound

Somewhere, in this labyrinth infinite and winding as time, this must belong.

My great-great aunt Ida had seven siblings. One was turned away at Ellis Island because of his deaf ear, the one he punctured to evade service in the Russian Army. Six went on to marry in New York City, raise children, become grandparents, then great-grandparents. But Ida was entirely erased from the narrative, never spoken about among her siblings. Later, my uncles discovered that Ida had been committed to a psychiatric hospital on Long Island, where she lived out the entirety of her adult life. None of us know why, though there are rumors she was molested by a family member and locked away.

The inheritance of this betrayal is lodged in my throat. Clenched fingers wringing at my thyroid, pulling at its wings. My great-grandmother, Ida’s youngest sister, felt it too. While her daughter, my grandmother, was at school, her mother cowered beneath a table, convinced that someone was coming soon to take her away. Trembling with a grief that could not be voiced.

Somewhere this must belong.

My grandmother was first hospitalized for colitis when my mother was fourteen. A splitting, searing pain in her lower abdomen. My grandmother spent the next fifty years of her life in and out of hospitals, her colostomy bag wriggling against her waistband. My stomach scorches with the acid of her temperament, the spiteful woman she became so young. The bitter drink of another woman’s life stolen away.

Somewhere this must belong.

My mother has dedicated her life to healing others. She treats patients holistically through nutrition and functional medicine, and maps out genograms to understand ancestral traumas. My mother has never ended a session on time. After a long day at the office, she spends evenings on the phone counseling friends, family, patients in emergency. Me. Her eyes gleam like galaxies, spinning with sorrow. I feel sometimes that she’s wearing a cloak threaded with a lifetime of women’s bodies: all their aches and inflamed joints, buried hopes, and mangled places. This cloak makes her a brilliant therapist; it’s why her empathy is infinite. But she’s worn the cloak so long it’s become her skin.

I don’t want to be like her—not the way she puts everyone before herself, not the way happiness is a foreign concept, or something that can only belong to others. I don’t want to wear her cloak. I want to wrest its fabric from my body and step into the future that belongs to my Hebrew name, my forgotten name. Rinamalka. Queen of Joy.

But I see myself spinning in her eyes.

Those galaxies called Mother. They will always be my first home.

Labyrinth as New Normal

I’m twenty-nine now. I have a full-time job, a live-in boyfriend, a demanding cat. It’s taken years, but I’ve stumbled onto the right balance of supplements, exercise, and nutrition. I laugh more than I ever have—mostly at the cat.

Still I always wonder what’s around the corner. How many days of crying are too many? Why is my stomach hurting? Is my exhaustion a signal of something besides bad sleep? Is bad sleep the first warning of my thyroid tanking? Is this anxiety mine or does it belong to the political climate? Is it disease or dis-ease?

Have you noticed yet that all I have are questions?

Labyrinth as The Cure (Redux)

These days when I call my mother seeking advice, she asks me a thousand questions about the supplements I’m taking, my bowel movements, my periods, then makes a myriad of recommendations—wants me to take more Vitamin D or Rhodiola or a pink powder that dissolves on the tongue to bypass the gut. Afterwards, I feel as though I’m emerging from plastic surgery, having sought one simple fix and emerging with a bruised-up body, marked with tape and pen in places I’d never noticed before.

She’s smart about these things and her suggestions often help. But sometimes I want her to be my mother, not my doctor.

One day she calls me, a little breathless. “Ariana, I think I have the answer.”

“To what?”

She goes on to explain a lifetime of my struggles in one chromosomal marker. A different kind of ancestral legacy. And there are remedies: herbs, vitamins, nutriceuticals. I’m too stunned to speak.

When I put down the phone, my living room hums with new potential. Our grouchy cat purrs in the sun. The plush sofa—the conversations my mom and I might have there instead. I thought I’d given up looking for an exit route from my problems, that I had settled on self-acceptance.

Still, something inside me itches to know: is this the cure I’ve been waiting for?

Labyrinth as “Something”

I cry a lot. Out of frustration, loneliness, hunger, rage. I cry easily and hard. At my boyfriend’s advice, sometimes I make myself punch pillows instead. Blankets. Soft, forgiving things. I pummel the pillows my mother bought me, transported across three boroughs to deliver.

Guilt cracks open my collarbone, knocks at the backs of my knees. My mother will do anything for me, yet I dream of escaping her labyrinth. The one we’ve built together.

Breath. Deflates. Fast.

Then Anger swells.

Anger about my condition. The health care system. Ignorant arrogant doctors. People telling me there is something wrong with me. Nobody knowing what the fuck is wrong with me.

My shitty childhood. My mother always trying to protect me. How I love her with the force of all the oceans. How love makes me punch pillows.

Afterwards I feel different. Not necessarily great, but calmer, like I’ve exhausted something in me. Even if I don’t know what “something” is. My cells reassembled like grains of sand after a storm.

Labyrinth as the Flow of Ink

Being inside a labyrinth is to essentially walk in circles, to make the same wrong decision again and again. Without a map, without a record of where you’ve been, it’s madness.

But this is why we make art: to lose ourselves and rearrange everything we thought we knew. The flow of ink maps the journey, revealing the paths we’ve traveled, the dead-ends we’ve walked right into, the portals we didn’t recognize.

Writing my way through these stories has been a labyrinth. A probing for the center, the shape of things, the way out. The Minotaur to slay. I might never know the name of my chronic illness or its root cause, how to ensure it won’t happen again. What belongs to me, my mother, my chromosomal mutations, my ancestors, my childhood. There may be no solution to this labyrinth, just as there is no way to solve an essay, because an essay is a voyage. The very act of writing is the thread. Hold on, wherever it leads. Your stories will tear down the walls before you and new ones will appear. Hold on. By the end, there will be a new maze, perhaps many, and you will be their maker. By the end, you’ll have mapped new worlds onto your body.

Hold on.

Labyrinth as the One Place

I always call my mother in the eight minutes it takes to walk between the subway platform and my building. The moment I emerge from the station stairwell, I pull her from my pocket, summon her voice with my fingers.

“I was just thinking about you,” she exclaims. “How was your day?

“Well… today was actually really hard. I’m struggling to write an essay about dependence and care and labyrinths, and about us…” I prattle on for seven minutes.

I always lose cell service in the lobby, so I linger outside my building until my fingers frost. When I step into the elevator, the call goes dead.

Every second ticks loud as my heart.

The doors push open and I call her back. She answers right away, and we start back up again. Then I realize. There is nothing for us to solve. Like Ariadne, my mother has given me everything I need.

“You know what, Mom? I think I just have to write my way through this.”

“Call me later if you want. I’ll be here.”

So far, she always has been.

I unspool the thread and descend into my labyrinth, the one place she can’t go with me. Where I can finally hear my voice.

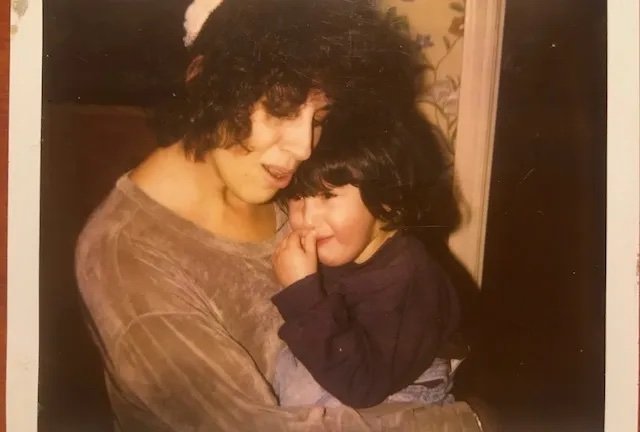

Photo Credit: Arya Samuelson

About the author:

Arya Samuelson was awarded CutBank's 2019 Montana Prize in Non-Fiction, which was judged by Cheryl Strayed. Her work has also been published in New Delta Review, Entropy, and The Millions. Arya is a graduate of the MFA Creative Writing program at Mills College and is currently working on a novel. She teaches online writing classes at LitReactor, Pioneer Valley Writers' Workshop, Sundress Academy for the Arts, and through her own teaching series, Writing as Ritual. Learn more at www.aryasamuelson.com