Photo Essay: Haiti Beyond the Headlines

By Ildiko Tillmann and Junior St Vil

Anne-Flore arrived early one dawn as the inescapable proof of the mercy of God. She was born in October 2019 during the height of what came to be known in Haiti as peyilok, a country-wide lockdown stretching over a period of about three months that was radical and revolutionary, but also violent, disorganized and ultimately trying for all parties involved. The early morning of Anne-Flore’s birth was similar to many others during that period. It followed a long, tension-filled night, the darkness of which was broken by barricade fires, and the light of rubber tires aflame. Whirling smoke suffocated the moon and the stars.

The wave of demonstrations that triggered the near complete internal blockade of Haiti started in September of 2019 as a popular movement against political and government corruption. It followed a year of heightened political tension and frequent protests. Participants demanded not only economic reforms, but also the enforcement of measures that would hold politicians accountable for embezzling millions of dollars of government funds.

At its inception, the movement had a wide support base that reached across political lines, although it was primarily led by younger Haitians, mostly artists and professionals. Over time, however, the civil movement was slowly captured by political interest groups, and the demonstrations morphed into a permanent, country-wide revolt, accompanied by gang-violence and looting, often fueled by political interest groups.

Life for everyone became emotionally and physically taxing. On most days, people were unable to go to work, unable to bring food home, unable to leave their houses or their immediate neighborhoods. Safety, with its varied meanings in different contexts, became the kind of luxury that many people in Haiti could not take into consideration during those days; you had to keep on living. Cars, motos and ambulances were held up at checkpoints and not allowed to pass. Smoke from burning tires, police tear-gas raids and the dust of unpaved streets filled the air, making it hard to breathe, burning your eyes. Shootings abounded, both random and targeted. Food and hospital supplies were sorely lacking. Under such circumstances, in a small medical clinic near her parents’ house, Anne-Flore was born, healthy. The immediate pain accompanying her arrival was only that of birthing.

In January 2020, peyilok eased up. It was the first full month when life appeared to return to normal, even if it became harder than before. Food prices doubled, people struggled to find work and businesses faltered. But schools and most government agencies opened again. An international jazz festival was successfully organized in Port-au-Prince. One could take a deeper breath.

January also marked the passing of ten years since the destruction caused by the 2010 Haiti Earthquake. While the earthquake was certainly much more immediately devastating in the area of the capital than the lockdown, the length of the emotional and economic stress the latter caused across Haiti is significant and the consequences still linger. Many people repeat the same refrain: “The people just cannot take any more. We are all at the end of our rope.”

***

In order to mark both the earthquake anniversary and the easing of peyilok, Haitian journalist Junior St Vil and Ildi Tillmann, author and documentary photographer, put together a photo essay highlighting daily happenings in Haiti. Their project marks a purposeful shift from a focus on destruction to a focus on life; it is an offering to those who have survived and who go on living every day. It is meant as a celebration of human strength, of effort and daily achievement in Haiti, while also a visual representation of the human condition which has echoes beyond its specific geographic location. The pictures included are not in any way exhaustive in their description of life in Haiti, they cannot be. In an effort to be as representative as possible, the authors put a deliberate focus on subjects that showcase the mundane, the routine, and the familiar. During the time of photographing the pictures, Tillmann made a conscious effort to move away from commercial images and photographic concepts used by journalists or non-profit agencies. Her work was guided by the words of her collaborator Junior St Vil:

“When I look at images in the press, or in advertising for NGOs, I see isolated stills of our lives, all in marketing technicolor. It is what sells: disaster, tragedy, suffering, and the foreign saviors who will help us become heroes one day. Except that the story of our heroism lies in our everyday struggles, in our strength of spirit and resilience, in our daily smiles, jokes, in empathy or love, in our reaction to acts of violence, pettiness and hate committed not only by foreign powers but also by our fellow countrymen. Our story lies in the heroism of being humans who have to face life according to the eventualities of their time and space. It lies in our art, and in our ability to not only see misery in places where photographers tend to focus on that aspect.”

Rainy season, on the road from Port-au-Prince to Cap Haitien. The rains usually last from May to November.

En route from Port-au-Prince to Cap Haitien, June 2019. Each time rains are heavy, the nearby river swells and the excess water floods this road with a strong current. When the water is deep, like above, cars are unable to pass this stretch of the road. The waiting time to make it across can last anywhere from a couple of hours to half the day. Local men and young boys guide, or carry, people and motorbikes through the narrow, passable parts of the water. Some are carried away by the current and drown.

Mural in Delmas 29, Port-au-Prince. The writing says: the art of unity.

Street vendors at night, in Delmas 29, a neighborhood of Port-au-Prince. In Haiti it is not uncommon to see beautiful stone houses alongside dilapidated buildings or even small shacks. In this area of the city many people produce their own electricity, mostly by solar panels or batteries. In Haiti, government supplied electricity is only available for limited hours during the night. In areas like this one the buildings usually have cold running water. Since tap water is not safe to drink, most people buy filtered water if they can afford to.

Young fashion models rehearse for a show.

Street in Delmas 29, at dawn.

Shoe shiners are a staple of the Haitian landscape. They walk around the towns ringing a bell to advertise their services.

Sunset in Kenscoff, after the rain.

A young girl from Saut d’Eau. The town of Saut d’Eau is close to a waterfall, considered holy by Catholics and Vodou followers alike. During the month of July, which is the time of pilgrimage, the town is full of visitors. Many Haitians living abroad travel back to Saut d’Eau during that time for spiritual reasons. The girl’s mother, a lively and welcoming woman, lives in the village by the waterfall, making her living selling home-cooked food.

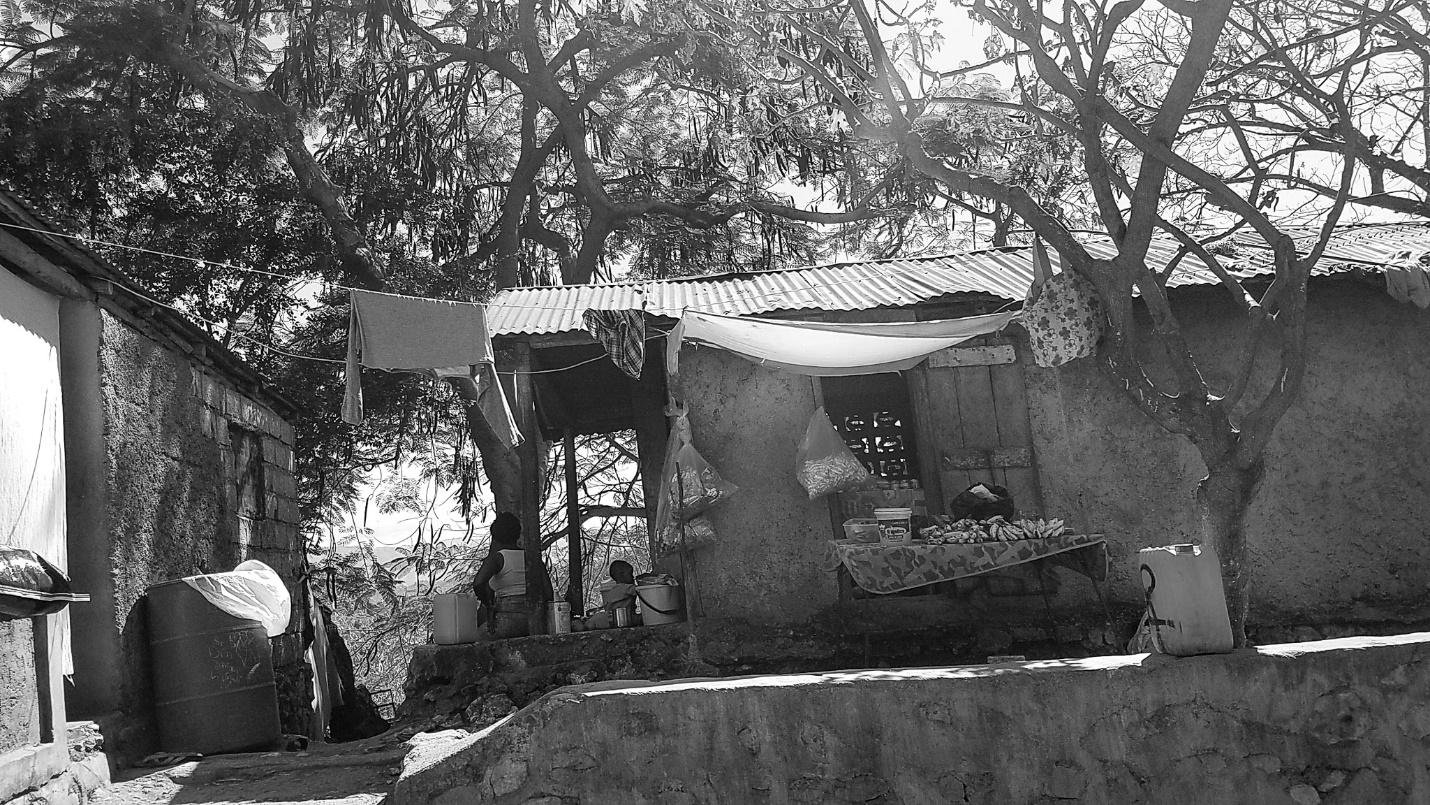

People living in a small community along the road from Port-au-Prince to Saut d’Eau. The woman in the picture operates a small stand where she sells fruit and some pre-packaged goods. Most local commerce in Haiti is channeled through small vendors.

A boy working for a guest house in Hinche, in the central plateau area of the country, carrying water on the horse. As the guest house does not have its own water supply for the moment, water is being brought from a nearby well, in large containers. The house was newly built.

Charcoal for sale. The majority of households in Haiti use charcoal for cooking. In urban areas where this is not practical, some people have stoves operated from a propane tank—a much pricier alternative. In many rural areas where charcoal is considered a luxury people use wood for cooking.

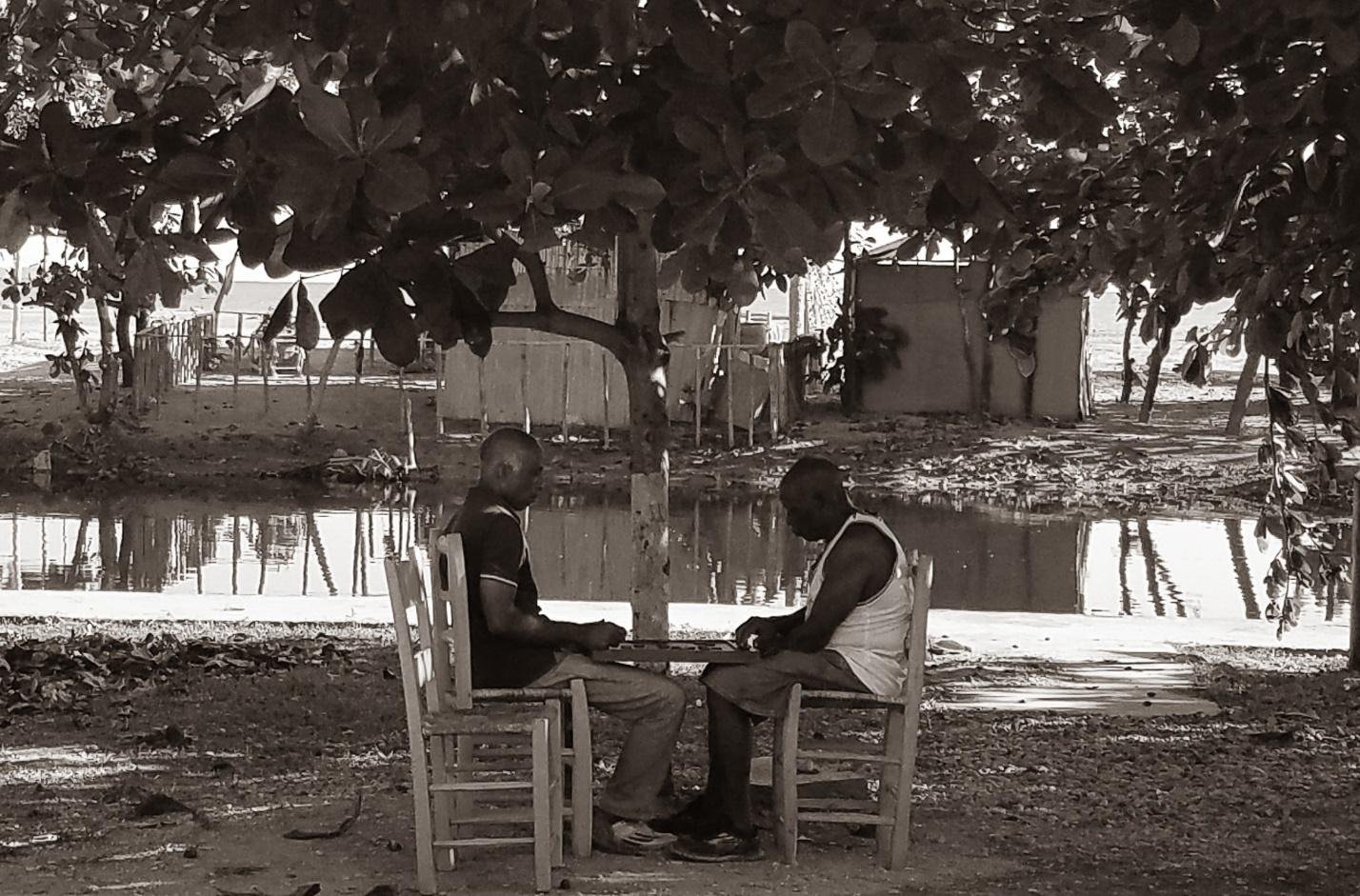

Beach area in the city of Les Cayes, early morning. Fishermen leave on boats to catch fish for the market or for personal consumption. Beaches and streets full of trash can be seen all over the country. Trash collection is rarely supplied by the government and it is not an area of interest for foreign non-profits. To ease the situation, people burn household trash in their yards or out on the street, but a lot is not combustible, such as tin cans and plastic bottles. This beach is a popular destination for people early in the morning. Locals go to the beach to collect water, to sit and read, or just hang out in the shade of the trees.

Two men playing backgammon on the beach near Les Cayes

Fishing boats at dawn near Les Cayes.

Kafou Kat Chemen, the Crossroads of the Four Roads, a major junction in Les Cayes.

A house in the city of Les Cayes with a water pump on the far right of the picture. Most houses in Haiti are being built gradually; construction continues as the owner can afford to pay for it. In many places, including the capital, there is rubble and random construction material piled up along the streets. None of this has any connection to the earthquake any more, it is a sign of intermittent ability to build and construct homes, as lack of employment keeps the majority of people without reliable income.

Hotel La Cayenne at dawn. The hotel owner, Gérard Chalvire, is a friendly, 86-year-old local man, a former pillar of the local community. He started building the hotel back in the 1960s, with a single pick-up truck, which he used to haul sand and rocks from a nearby mining area. Later, he hired an architect to draw up plans for the building. Similar to most business owners in the country, Mr. Chalvire has suffered severe consequences over the past year, particularly during the months of the peyilok. When asked about varying reasons for slowing tourism, such as the earthquake of 2010, or Hurricane Matthew in 2016, which hit the area of Les Cayes particularly heavily, he smiles and says: “Those things are bad, but you rebuild. You can move on. This political instability, the barricades and shutdowns, are worse than ten hurricanes put together. Everything is unpredictable, everything is blocked. Haiti is in a very deep hole right now, and we don’t know how to find the way out of it.” Since the lockdown was lifted, the hotel pool is being used to offer swimming lessons to local children and adults.

An old restaurant near the capital, Port-au-Prince. The atmosphere and the details of faded glory recall its past beauty. It still opens and hosts people in the evenings, with occasional musical events. In the past, the restaurant was part of a guest-house complex, a popular destination for people from the capital. The peyilok and the political instability of the past year have had profound consequences for restaurants and most local businesses, including car rentals, small hotels, guest houses and Airbnb-listed properties. Many were forced to go out of business completely, or temporarily close and let their workers go. All the people working these semi-permanent jobs lost their livelihood, or have been going without income for months.

A man preparing and selling food on the street in Port-au-Prince.

Two Haitian journalists, Junior St Vil and Rodli Saintine, in a small restaurant in Port-au-Prince. The place features simple but excellent local food, mostly meat, rice and plantain, cooked or fried in large dishes on open fire. The first floor bar offers drinks and has a small TV screen. The light in the bar only comes from the parking lot of a nearby supermarket.

Junior St Vil, in the front, has periodic contracts with foreign journalists, missionaries or academics. He dreams about producing his own radio show that would discuss cultural and social issues in Haiti and around the world.

About the authors:

Ms. Ildi Tillmann is an author and documentary photographer, born and raised in Hungary, currently living in New York. Over the past two years she has been photographing and writing her own free-lance project: Lives in Revolution. She covers Haiti through personal stories that look behind media headlines. Previous publications include: The Caribbean Quarterly; The Caribbean Writer; The Haitian Times; Columbia Journal.

Website: https://www.ildikotillmann.com/

Instagram: tillmannild

Mr. Junior St Vil is a Haitian journalist and translator who lives in Port-au-Prince. He has worked as a missionary group coordinator/interpreter and as a producer for foreign news outlets and agencies, such as The New York Times, Agence France Presse and National Geographic. When conditions in his country improve, Mr. St Vil plans to run his own radio-show that would cover culture, politics and education.