In Defense of Cancel Culture

By J.C. Hallman

I

If you’re all worked up about what the now infamous Harper’s Magazine piece of summer 2020, “A Letter on Justice and Open Debate,” is either saying or suggesting about “cancel culture,” then you might be interested to learn that the Supreme Court already ruled on this—sort of—in a notable First Amendment case, U.S. v. Alvarez (2012).

Here’s the gist: Alvarez lied about receiving the Congressional Medal of Honor. He was prosecuted under the Stolen Valor Act of 2005, it went to court, and after a protracted battle the Supreme Court ruled that Alvarez’s First Amendment rights had been violated. Lying about receiving military honors was protected speech. (In 2013, the Stolen Valor Law was replaced with a law that made it illegal to lie about receiving military honors with “criminal intent.”)

What’s relevant to the Harper’s piece is a portion of Justice Kennedy’s majority decision, in which he was joined by the Court’s left wing—Kagan, Sotomayor, and Ginsberg—in a lopsided 6-3 vote. Alvarez’s bad speech, Kennedy argued, should not be prohibited because he had already been “ridiculed online.” There was no need for an additional curb on his speech, as “counterspeech” full of “outrage” and “contempt” had revealed Alvarez to be a “phony.” Other “false claimants,” Kennedy went on, would likely befall a “similar fate.”

It’s clear that the Court is addressing the same kind of public rancor that the Harper’s letter now wants to tamp down: so-called “cancel culture.” And what’s made clear by the Court’s decision is that if you’re going to cancel “cancel culture,” then you’re going to have to be prepared to do something about free speech, because the Court has already ruled that “cancel culture” serves as an important check on speech in the public sphere, creating serious consequences for those who disseminate lies or spread objectionable views. (Consider this from a judicial opinion from earlier in the movement of U.S. v. Alvarez through the courts: “The right to speak and write whatever one chooses—including, to some degree, worthless, offensive and demonstrable untruths…is, in our view, an essential component of the protection afforded by the First Amendment.”)

II

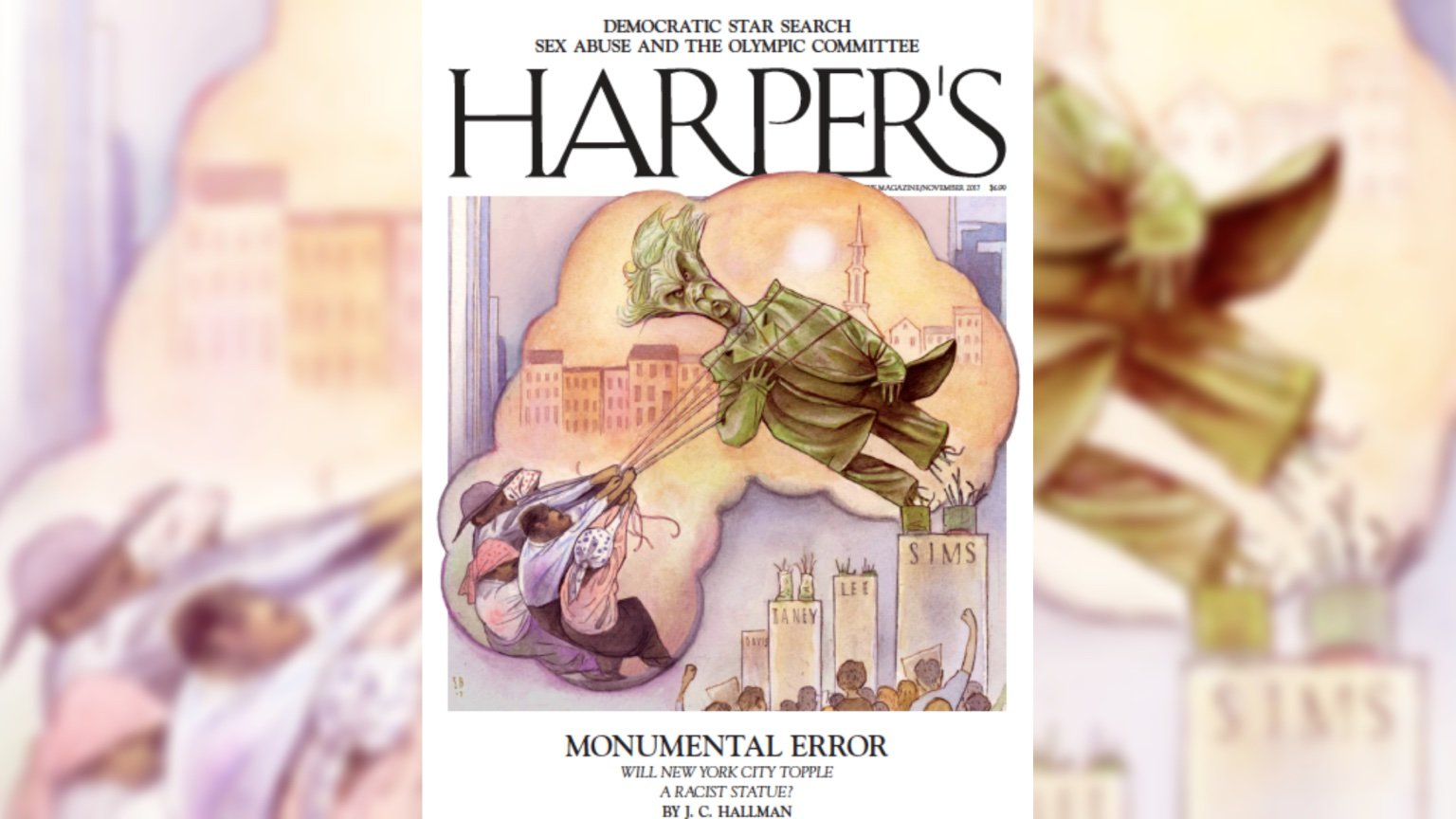

In 2017, I contributed the cover story for Harper’s November issue. It was an article about the statue of Dr. J. Marion Sims in Central Park. I admit it, I wanted to cancel him.

Actually, it worked. I was far from the only voice involved, but the statue was removed in early 2018, in a groundbreaking and precedent-setting action for New York City. At that moment, Harper’s found itself—perhaps inadvertently—at the forefront of helping to nudge the world over to the right side of history. We’ve all seen the good, in the form of new emphasis on the pain of oppressed persons in the face of public monuments of all kinds, that has come since then.

So, I admit that I was a little surprised when Harper’s did not ask me to sign “A Letter on Justice and Open Debate.” After all, our piece had been an excellent example of—I think—the exact sort of thing the letter is trying to be about: the power of carefully reasoned debate to shape the world.

Anyway, I wouldn’t have signed it.

The Harper’s letter is a group-authored complaint about complaints that arise from groups. It hopes to strike a civil tone that stands in contrast to abrasive voices that—so they claim—act as a form of censorship. However, as others have noted, the quality of the writing of the letter is tepid, affectless. It lacks the feel of a human soul behind it, and this leaves it vulnerable to accusations of paying lip service to causes about which many people care greatly.

The letter attempts to thread some difficult needles, and in doing so it makes some pretty basic mistakes. I suspect that many of its signers, safe inside a herd, did not fear that these errors would be laid directly at their feet.

First, its initial paragraph cites an “intolerant climate that has set in on all sides.”

This is classic bothsiderism. Or allsiderism. And it’s false. Institutionalized policies of shaming, name-calling, and professional sabotage as an ordinary mode of conducting business and government, already normalized on the far right, is nothing like the semi-organized actions that emerge from individuals—those not likely to be asked to sign open letters—expressing ridicule and outrage from the opposite side of the political spectrum.

In other words, one “side” is government-mandated propaganda, and the other “side” is organic protest—we might call it rhetorical picketing—from people who are more accustomed to having no voice at all. The two are hardly a common phenomenon.

Also, the letter claims that “the way to defeat bad ideas is by exposure, argument, and persuasion.” This is a slightly ornamented take on what one sees in Supreme Court arguments like U.S. v. Alvarez. The solution to bad speech is not censorship, but more speech.

Problem is, that’s not what the letter winds up doing, despite what it says. In lashing out at “cancel culture”—even though it never says the phrase—the signers of the Harper’s letter are, in fact, making the most genteel and duplicitous of attempts to staunch others’ speech. In keeping with the decision of U.S. v. Alvarez, “cancel culture” is not a threat to free speech. Rather, it is an example of it. One that serves an important societal function, to boot.

Now, I can hear your hesitation. U.S. v. Alvarez is about lies, you want to say, whereas the Harper’s letter is about expressed opinions. True, but I suspect that each of us would be just as comfortable heaping ridicule onto a man who makes false claims to military honors as we would be to ridiculing a man who expresses the opinion, “I love Hitler!”

That’s an extreme example, of course. And it’s one that is likely to result in a relative consensus. But not every “opinion” is so clear cut, and it’s on this point that the Harper’s letter makes its gravest error. In describing the sorts of “censorious” phenomena hobbling the world of letters and publishing, the letter writers claim to be able to recognize those incidents which are not particularly severe. Those which are met with “hasty and disproportionate” responses. Tallied up among the unfortunate victims of over-reaction are books of “alleged inauthenticity”; journalists writing about “certain topics”; “perceived” transgressions of speech; and organization heads that are guilty only of “clumsy mistakes.” The letter writers appear perfectly comfortable deciding for all of us just how offensive something is, or whether it is offensive at all. They wind up advocating a return to a “culture” in which those who are judged to be uninformed or uninitiated are discouraged from expressing opinions about whatever they might find to be racist, bigoted, or otherwise objectionable.

A single example may make the case. The letter writers worry about “professors [who] are investigated for quoting works of literature in class.” This, presumably, is a reference to novelist Laurie Sheck, who came under fire not long ago at The New School for reading aloud to her classroom passages from James Baldwin that include precisely the racial slur you’re now thinking of.

Now, to be clear, I agree that there are utterances of words, and there are uses of them, and they’re not the same thing. But that’s not what’s at issue here. What’s at issue is that a student heard this word, and was injured by it. For the student, it didn’t matter that it was in a quoted piece of literature. The word hurt. But rather than listen to that pain, and acknowledge it, the Harper’s letter writers simply announce that it is wrong to feel that thing. They cram the complexity of the student’s emotions into a sentence fragment, and in a dry tone of blasé insouciance, they say that such a response is inappropriate. Presumably, the student should simply remain quiet.

III

I suspect that the true problem right now is bigger than what the Harper’s letter sets out to concern itself with. The real culprit is neither “cancel culture,” nor thin-skinned authors signing group letters. The problem may be—steel yourself, now—the First Amendment itself. Truth be told, the First Amendment today is like an old website plagued by a constellation of dead links. “Obscenity” is still an official prohibition on free speech. “Fighting words” is yet on the books as verboten in the public sphere. We’re long overdue for an overhaul of the code for a text that was written, presumably, just prior to that of the Second Amendment. How many of us would like to see some hard thinking about the wording of that one, too?

First Amendment issues undergird problems we’re seeing well outside the literary ivory tower. Without stating it directly, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg and Twitter’s Jack Dorsey have, until recently, been relying on the “more-speech-is-the-solution” argument in their response to the quandary of false speech on social media. That didn’t make anyone happy, so now changes are underway. I applaud those changes—but for God’s sake, tread lightly.

Perhaps it’s as simple as noting that technology has made speech so fast and nimble that our old conceptions of how speech functions simply don’t apply. Propaganda and lies are prevailing, and it’s affecting the ability of the United States to be the world leader it once was. Even the Harper’s letter writers seem to acknowledge that part of the problem is just how fast a shaming campaign—free speech or no—can do its job.

It’s not that “A Letter on Justice and Open Debate” is wrong. It’s that it’s unimaginative. It applies tired rhetorical tropes to a problem that is evolving election by election, year by year, news cycle by news cycle. I’m tempted to dismiss it with a simple, “Okay, Boomer,” because despite the fact that a number of its signers are young, its basic message is fundamentally backward-looking. It offers no practical solutions, other than to suggest that some people really just need to get a grip. In the end, however, I do not think we should reject the signers of the Harper’s letter. Regardless of how they were chosen, the letter writers are as impressive a group of folks as you are likely to find. What we need from dazzling imaginations like these is something more than a simple call to make the literary world great again. Rather, we need these robust minds to apply themselves to a problem much larger than the one they signed on to address.

This piece is an op-ed and does not reflect the opinions of the Columbia Journal or Columbia University, or the School of the Arts.

About the author:

J.C. Hallman is the author of six books, and a recipient of fellowships from the Guggenheim and McKnight foundations. His dual biography of diabolical surgeon J. Marion Sims, and the young enslaved woman known as Anarcha, will appear in early 2022. He sort of lives in New York, and can be reached through JCHallman.com