NONFICTION – Catch, Release, Breathe by Shannon LeBlanc

By Audrey Deng

Nonfiction by Shannon LeBlanc

—

One

“What do you mean you can’t swim without those things?”

Uncle George doesn’t wait for me to answer. In a squelch, the orange arm floaties are tossed aside. I am high in his calloused hands. When he throws me, I soar in the blue summer sky until the water swallows me with a bite against skin.

Underneath, my arms circle helplessly. The bottom of the pool feels slimy, cool against the bottoms of my feet. Pressure builds behind my eyes, in my ears, deep within my lungs. I cannot breathe. There are hands around my waist, and we propel upwards towards rays of sunlight. At the surface, I gasp and choke while my uncle paddles to the pool’s side.

I hear my mother’s voice first because it is angriest. She is calling Uncle George a fucking idiot for throwing me, a four-year-old, into the deep end. Uncle George hoists me onto prickled concrete that scratches my bare legs. My mother yanks me close and tight against her smooth skin. I wipe snot on her shoulder.

“I could kill you.”

“She knows how to swim now.” He says, pulling himself out of the pool. Water rolls off his skin, staining ovals onto the ground beneath his feet.

“Again!” I say, reaching arms toward him.

I do not understand what my mother does; I do not fear water like she does. I never will.

“See?” He shoves floaties back onto my biceps.

“Fine,” she thrusts me at my uncle, “just make sure you jump with her this time.”

Uncle George grins. I giggle. We jump on three.

Throughout my life, I will dream of flying through the air, waiting for the bottom to come, waiting for the moment when hands reach for me, find me, carry me home.

Two

Dense steam clouds my view of the shower stall, its swaying shower curtain, my chipped blue toenail polish, the plastic caddy and shampoo bottles. It is very early for a Saturday morning in college; I know I will not be disturbed.

The new, white loofa in my hand is filled with coconut-scented soap, and I press into my eighteen-year-old skin and over the bruises of fingertips branded onto my body. I scrub each spot until I imagine the blue-green ovals have disappeared. I work from arms to my inner thighs, wanting each swipe to erase the imprints of his stubby hands, palms over mouth, jagged fingernails catching the thin skin covering hipbone, the memory of pressure around my throat. I only stop to squirt more soap on the loofa and I continue until the water is cold and the container empty. This shower has become my vehicle to forget, and I will try to do so for years after this moment. This scouring is my penance for the night before; water is a baptism. I will wash away evil, remove sins, become pure.

When blood trickles from raw, red patches and onto the floor before whirling into the drain, I know I have been reborn.

Three

“Go play in the water,” The college distance swim coach says while he points at the diving well with his clipboard and its narrowly written numbers, splits and times of races over the three-day swim meet in the midst of a Pennsylvania winter.

I turn to march to the diving well. I am twenty and alone, cold, tired.

“Remember to have fun!” He orders my back that is etched with the imprints of a racing suit.

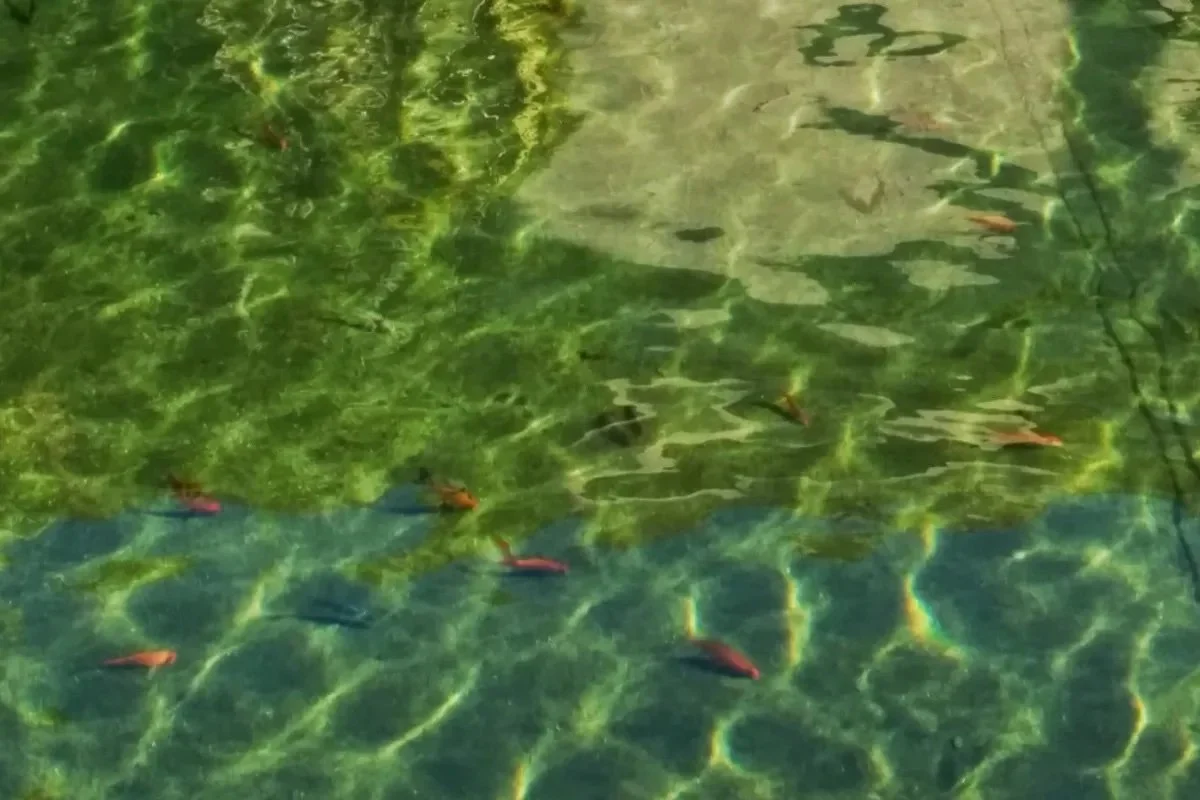

The diving well is packed with people, and I submerge until my ears pulsate in pain. Above, swimmers from various teams kick, pull, rotating back and forth like ants marching to and from a hill. I watch their obedient rhythms before surfacing, inhaling air that is chlorinated and heavy. I continue to dive and surface until my toes are numb and my lungs ache. I’m not properly preparing for my race and I don’t know why, but I’m starting to think it’s because I cannot remember the last time competitive swimming was fun. On my last plunge, I reach the bottom only for a moment before I kick off, eager for air.

At the edge of the diving well, I push myself upward on my elbows, imprinting miniscule tiles into my skin. In my team’s corner, the coach is staring at his stopwatch before darting his eyes to the race about to begin in the lap pool.

The coach nods when I return and wrap myself in a sodden towel. A teammate throws me orange. In a few hours, I have another race.

Across the pool, there is silence as swimmers take their marks, backs hunched toward the natatorium’s ceiling, toes wrapped around the square block, quads ready to spring. There is a flash of light, an electronic beep, and eight bodies are soaring through the air and into the pool. I will be there again after a long wait. There is no fun in this waiting. Not fun in water anymore. I am cold and hungry. Between my teeth, the fruit bursts both tangy and sweet.

“You remember now?” The distance coach says to me, focus never leaving the pool. I nod and turn away from the race, from my teammates and all our opponents, from him, from the water.

I am alone.

Four

“You a swimmer?”

“I used to be,” I say to the elderly man in the lane next to me.

We are standing in separate lanes of the gym’s murky pool. The air is thick with chemicals. Another swimmer creates waves in a lane by the wall. It is early morning on a winter day in Massachusetts, and most of the world is still sleeping while I try to revive my old life, my old self.

The older swimmer studies my faded, but still too tight, racing suit, the goggles perched on my forehand, the kickboard at the lane’s end. His eyes crinkle when he pushes his own goggles to his face, trapping the rubber seal so water won’t leak inside and blur his vision. Behind us, the second clock notes each escaped moment.

“You still are.”

He ducks and is halfway down the lane before I think to disagree. I watch the arc of his arms, the bubbles trailing his feet, the rhythm of his head when he turns to either side to inhale the stale air.

I wait, place goggles over my eyes, and move forward to a rhythm I know: submerge, extend, glide, catch, release, breathe.

—

Shannon LeBlanc has an MFA in creative writing nonfiction from Boston’s Emerson College. She lives in Louisville, Kentucky, and teaches English at a private middle school.