Artist Profile: Rowan Wu, Painter and Barnard Student, by Zoe Marquedant

By Zoe Marquedant

Philosophy Hall, by Rowan Wu

Editor’s note: Rowan’s exhibition celebrated its opening on Thursday, November 3rd, at 6pm at Birch Coffee on the Upper West Side. More info here. See more of Rowan’s art on her instagram and website.

What do we do for our own sake? Binge watch all of Westworld in a single weekend, eat an entire box of mac and cheese in one sitting, major in nonfiction? Few of us can say that we are truly productive in these actions. Sure Netflix may be comforting and relaxing, but how good is it for us actually?

Rowan Wu (www.rowanwuart.com), an Urban Studies major at Barnard, devotes herself and her spare time to her art. Not for credit, not for followers, but for herself. “I’m just doing what I love,” Wu says with a shrug.

Bethesda Fountain, by Rowan Wu

To her, painting is a natural response to the mounting pressure put on a college junior. To counteract that stress, Wu spends hour blocks perched in cafes or on steps, trying to conjure in watercolor “the creative spirit” of her subjects.

“I’m just doing what I love,” Wu says with a shrug.”

Rarely depicting people, Wu focuses instead on landmarks which “capture New York’s identity,” an easy task in a city with such an iconic skyline. However, Wu isn’t concerned with the exactitude of duplicating that scene. “My lines aren’t perfect.” She says, her finger following the ceiling of a building that seemed dashed across one of her paintings. Instead of a carbon copy, she aims rather for “the energy of the city. It’s soul.”

How does she determine what or where that soul is? It comes down to “what resonates with [her].” Most recently, this has equated to simply: “All the parks.” Everyone loves a lazy afternoon on the lawn, but why such enthusiasm for such a specific subject? “I worked for Central Park.” Wu explains, having interned there during the summer. She worked in The Bramble, learning not only about park management, but also about the types of trees around her. This is where Wu learnt horticulture and the names of what she was sketching.

Her internship in conjunction with her studies led to Wu’s interest in New York’s green spaces, its “smaller squares,” and “how [its] people care for outside spaces for themselves.” She became intrigued by the urban history of New York and finds it increasingly “rewarding to learn about [the] growth of city” in both her academic as well as artistic pursuits.

With these goals in mind, Wu began “pretty simply.” She didn’t see herself as anything but as “an observer, a part of a whole living here.” With a keen, yet thoughtful eye, Wu began to capture the city and city life in whimsical watercolors, trying to encapsulate “the liveliness of living in [the] city” into her paintings.

Central Park Fall Foliage, by Rowan Wu

Not formally trained, Wu considered herself “an amateur.” Her friends translate this as Wu “undervaluing herself,” but even now she maintains that she’s “just doing it for me.” It was easy to be this ardent and dedicated during those summer months when time was plenty and everything was leafy. Now that school is back in session, Wu sees her art, particularly her pictures of campus, as “a bridge between academic and public space.”

“It was easy to be this ardent and dedicated during those summer months when time was plenty and everything was leafy.”

With a summer full of “so much inspiration” and sketchbook brimming with paintings, Wu began posting to Instagram. Amongst her friends, her newfound enthusiasm in art was met in some cases with the somewhat tired response of, Oh! Draw me!

Although some of her work does include people, Wu owns up that, “I don’t love portraits. You can’t fudge detail[s] with people.” Wu points to the rough shapes that, together, equate to a cityscape on the page. “People still recognize a building.” Focusing on buildings and scenes, Wu slashed lines that together until they formed Yankee Stadium, Washington Square, Jacob Riis Beach, The Dakota, Grand Central Station and other iconic sites.

Wu points to the rough shapes that, together, equate to a cityscape on the page

It was “not about technical skill” or “efficiency and accuracy,” but rather “about the personal pursuit.” Still figuring her Art out, Wu hasn’t started stressing herself over the perfection of her lines or the price points for commissions, just yet. “I have no obligation to draw. I just draw what I see.” She says, although admitting she still asks herself, “Is this what I want to do? I don’t want to lose the drive for day out,” as she becomes increasingly involved with her work.

“It’s not about the materials.” She pulls a Uni-ball from a nearby pencil case and describes it as, “just one that I found.”

While she is protective of her inspiration and intention, her entire approach remains practically casual. Wu isn’t the kind of artist to spend months torturing herself over which pen to use. “It’s not about the materials.” She pulls a Uni-ball from a nearby pencil case and describes it as, “just one that I found. The pen seems natural. There’s a linear hardness to it.”

When sitting down to a painting, she chooses an equally nondescript pencil to first gather the general sense of scale in her sketch. With line grey graphite lines, she looks for “how tall buildings are, how they intersect.” She then goes over her estimations in a loose pen. The benefit of this is: “I can’t erase. It’s there.” The permanence of ink helps Wu be “less of a perfectionist.” She instead insists on being satisfied with “just drawing what I see. Just going for it.”

Charleston, South Carolina, by Rowan Wu

Neither does she approach watercolor with any kind of formal intention. Landing on the medium in particular was more a process of elimination than a conscious choice. “I’m bad at acrylic.” She admits. Watercolor more met her needs. “It’s fast and dries really quick.” It’s also a more “flexible, fluid medium.” When paired with her ink outlines, she finds the watercolor adds a “second dimension of depth and color.”

It isn’t the strictest of formulas, but for now Wu says, “I’m comfortable using what I like to work with.” Wu admits she “hasn’t experimented” much beyond these materials or what they can do. She had however learned to care for the weight of the paper and not draw on both sides, now with the possibility of “I might have to display this one day” weighing on her mind.

“with the possibility of “I might have to display this one day” weighing on her mind.”

Wu produces a sketchbook, 5.5″ x 8.5″, with a silver-sharpie skyline drawn across its front. Although the cover may depict Manhattan and with it New York’s iconic bridges, its first page is devoted to Wu’s beloved Boston. Originally from Massachusetts, the state features intermittently through the dozens of paintings, each given their own page and signed dutifully at the bottom.

She then pulls out a case of watercolors. “It’s very portable. The pens carry water in them.” This eliminates the need for a water cup or much else besides her palate and paper. The compact case fits in one hand and holds two ‘pens’ as well as about a dozen bricks of paint. “I try not to relying on the colors try gave me.” She instead tries to find her own, sometimes painting with a drier brush to better “determine the mood of a piece.”

But before Wu can perfect her picture and temper the colors together until the right shade emerges, she has to pick a spot to draw. “You have to limit the space in which you can see. Look for where the picture is cropped” She says, holding the sketchbook up, to show a possible subject’s framing from her perspective several feet away. “You have to think what to show. A picture is as much about the details you leave out. What foliage you include.” Wu gestures at the expanse of green atop stick like branches that represents the treetops in a sketch of Bryant Park.

“A picture is as much about the details you leave out.”

The whole process from pencil to “takes exactly an hour.” During that sixty minutes, she doesn’t check her phone and is luckily otherwise undisturbed. “Most people tend to leave you alone.” She says. After the hour, she emerges “very drained, with a kind of manic look in [her] eye. Feeling like [she] just took a very long test.” Thankfully, the end of a painting also comes with “the endorphin rush of a long run.”

As far as future topics, Wu has “an artillery of places” that she’s been meaning to paint. “Sometimes it’s ‘I’ve been here and I want to go again.’” Currently, Wu says, “I want to take advantage of temporality. Like the fall colors.” Her painting of the New York Botanical Gardens highlights the canopy of greens and spring blooms that have since faded.

More recent sketches show the red and oranges of autumn. “Adding color is very rewarding. It’s gritty without it.” Sometimes the absence is contrasting and Wu leaves sections purely in pen, as in a recent painting of the lake at Central Park. For the most part, Wu says, “I match what I see. Although I admire people who can get creative.”

Botanical Gardens, by Rowan Wu

In trawling for more places to sketch and artists to emulate, Wu has found an online community and, with them, a trove of inspiration. Creators in different cities — Paris, Vienna, Prague, Barcelona — all in places she’d love to see and sketch. “A sketch-cation” she calls it, on which she could paint and study “how the architect informs the birth of those cities.”

In Europe specifically, Wu wants to try to capture “the way they use space.” It’s easy to imagine cramped apartments and tapering sidewalks along cobblestone streets, but capturing it specifically would be a welcome challenge. “There’s an enchanting density.”

It was in such a foreign city on a recent trip to China that Wu began her journey as a sketch artist and led to her current concentration in “live sketches,” as she calls them. “There’s something about Asian cities. Chinese landscapes. The density, the sheer number of people, the oppressive heat. [A city] growing at a rapid rate.” All this chaos, and perhaps its relative parallel to New York’s own writhing mass, peaked Wu’s attention.

She dreams of returning and sketching cities like Singapore and Tokyo, where “modern meets old” and “the introduction of technology is seen in skyscrapers and billboards.” Wu’s carried this fascination with the minutia of historic districts and industry architecture back to New York, where while walking around, Wu often pauses to look up with glee, much to the chagrin of faster-paced friends who bemoan, “Stop freaking out about the cast iron!”

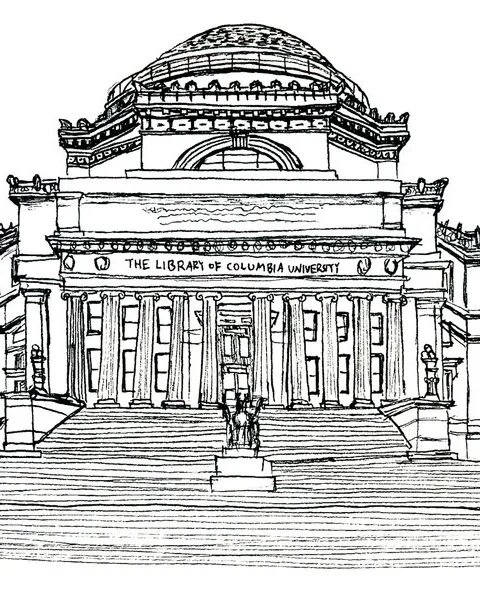

Low Library, by Rowan Wu

Wu has found one or two friends who are in a similarly artistically-inclined place as her. Her “Art Insta-” family. A group of creators, who although have different styles express similar interest in their pursuits. So what happens to this digital community, in real life? “It’s a bit like a first date.” Wu says, describing meeting one such online buddy to sketch Columbia’s replica of Rodin’s “The Thinker.”

They both captured the subject, but “not in same way, not with same purpose.” Still, Wu says, “It’s nice to know that someone else relies on the visual to express the self and escape from this stress culture.” She waves her hand in the air, gesturing to the other occupants of Lerner, diligently studying around her. “It’s important to have these outlets.” To do something “purely for its own sake.”

Wu is lucky to have found such a positive response given that the Internet and its comment sections can be unforgiving. She remembers one recent note, left lovingly on one of her posts. “It was in Spanish. I was like ‘What?’ I had to ask my friend to translate.” The message was of encouragement, unexpectedly from thousands of miles away.

For her, Wu says social media sites, like Instagram, have “encouraged me.” She sees her social media handles as ways “to share and publicize work as well as to gain recognition outside of Columbia community.” They’re a “medium to get art out and be part of a community of artists online.”

And word of Wu has definitely gotten out. She recalls how interest “really kicked in over the summer.” A fateful re-posting (“re-gram”) of one of her illustrations by Central Park’s official Instagram account resulted in a surge of Likes, Re-grams, and additional followers. It was a watershed moment for Wu’s online popularity. “I could feel something was about to change.” She remembers.

Suddenly commissions started coming in. Wu had to learn to post her paintings strategically in, accordance with the timing for potential followers’ social media browsing habits. Months later, the shock still hasn’t worn off. “I need business cards now. Like, what?”

“I need business cards now. Like, what?”

Most recently, Wu landed a gallery opening at Birch Coffee’s Upper West Side location. There, her artwork will be on display for friends, followers, and coffee drinkers alike. The show starts with an opening party on November 3rd, which comes at an opportune time, that week also containing Wu’s 21st birthday.

Philosophy Hall, by Rowan Wu

With this opening approaching, Wu’s art has officially and, perhaps, irreversibly expanded beyond her personal use. “I don’t know where this is going,” she admits, but that’s not stopping her.

As she packs her watercolors and tools away, she nods, open to the possibility of stopping somewhere to sketch in-between errands and reading. For her it isn’t a chore or more work. “It’s the best kind of self-love.” She says.

To everyone clicking through Facebook or scanning the Journal instead of starting that book/script/painting of their own, consider the affirming words of Rowan Wu: “You can. The only thing stopping you is yourself.”

About the author: Zoe Marquedant is an MFA candidate in nonfiction at the graduate writing program of Columbia University’s School of the Arts.